# Symbiotic

> Symbiotic is a generalized shared security system enabling decentralized networks to bootstrap powerful, fully sovereign ecosystems.

## **Universal Staking**

Universal Staking is more than just restaking. Instead of merely reusing staked assets to secure multiple networks, it introduces a flexible coordination layer for sharing collateral across a wide range of use cases beyond Proof-of-Stake (PoS) implementations.

### **Traditional Shared Security**

At its core, shared security is the alignment of incentives, either horizontally across multiple participants or vertically across layers within the same system. This foundational primitive unlocks a modular design space. Horizontally, it enables networks to tap into pooled economic security, accelerating decentralization in a capital-efficient way. Vertically, it turns existing tokens into multi-purpose assets, like using governance tokens to secure sequencing layers.

By making data around validator performance, node distribution, operator quality, and security effectiveness transparent and programmable, it reduces coordination friction and lowers the barrier to deploying decentralized infrastructure.

But shared security is just the beginning. While it allows networks to inherit trust more efficiently, it is often implemented in narrow, use-specific ways. What comes next is a broader coordination layer, one where capital can flow dynamically between networks and applications, supporting diverse forms of security, utility, and risk underwriting with customizable rules and shared infrastructure.

### **The Universal Staking Framework**

Through engaging with hundreds of builders over the last few months and launching 16 networks on mainnet, we realized that the underlying concept of shared security can be leveraged in ways far beyond what restaking and traditional shared security infrastructure envisioned. What started as a way to coordinate stakers and networks around Proof-of-Stake security revealed a broader design space for incentive alignment and capital coordination.

Universal Staking, as developed through Symbiotic, builds on this insight. It generalizes the shared security model into a modular coordination layer that can be applied across use cases, not just for securing consensus, but also for underwriting risk, bootstrapping new protocols, and aligning incentives between diverse actors. For example, lending markets can use it to backstop bad debt, enabling stakers to opt into specific risk profiles with customizable terms. This is no longer just about securing networks, but about unlocking new forms of programmable trust between capital and applications.

While the chart below shows that staking has outpaced total crypto market growth since 2021, it also underscores how early we still are. Symbiotic is built to push beyond traditional staking by allowing projects to bootstrap security from external assets, design modular staking systems, and apply staking to use cases like risk underwriting and insurance. The goal is not just to scale staking’s footprint, but to evolve it into a coordination layer for capital, security, and incentive alignment across the onchain economy.

#### **Key Metrics**

* Staking grew from 2.99% to 11.56% of total crypto market cap since 2021.

* Restaking emerged from 0 to nearly 1% of total crypto market cap in under 2 years.

* While crypto market cap grew 22% YoY since 2021, staking and restaking quietly doubled that at 45%.

* At the current trajectory, staking + restaking will reach 50% of crypto market cap in \~8.4 years (around early 2033).

*data from [**DefiLlama**](https://defillama.com/), [**StakingRewards**](https://www.stakingrewards.com/), and [**Coingecko**](https://www.coingecko.com/)*

### **Universal Staking Use Cases**

#### **Native Staking**

Native staking refers to the use of a protocol’s own token to secure and coordinate activity within its ecosystem. While traditionally tied to Proof-of-Stake consensus or governance, Universal Staking reframes native tokens as programmable trust assets, acting as flexible primitives for enabling coordination, enforcing rules, and aligning incentives across modular systems.

**Expanded Utility**

* Programmable Trust Layers: Native tokens are no longer limited to gas payments or voting power. They can encode slashing conditions, distribute rewards, and coordinate behaviors across trust-minimized components.

* Incentive Systems: Models like vote-escrow and revenue sharing allow protocols to design long-term alignment between users, contributors, and applications.

* Composable Security: Projects such as Hyperlane show how native staking can be combined with staking on Symbiotic to enforce custom slashing logic and strengthen inter-network security assumptions.

* Mesh Security and Cross-Ecosystem Coordination: Native tokens can participate in broader security meshes, where the same asset secures appchains, messaging layers, oracle networks, and more, all at once.

**Example**

Hyperlane uses HYPER for native staking to encode programmable trust logic within its modular interchain stack. Through Symbiotic, HYPER holders can stake their tokens and secure core components like ISMs. For a deeper look into how Universal Staking powers native trust models, [**check out our blog post on Hyperlane.**](https://blog.symbiotic.fi/hyperlane-native-staking-powered-by-symbiotic/)

#### **Insurance and Guarantees**

Universal Staking enables programmable collateralization to underwrite risks beyond protocol security, e.g., lending, insurance, or structured financial products. Capital can be orchestrated through slashing conditions, acting as automated enforcement mechanisms.

**Expanded Utility**

* Bad Debt Protection: Inspired by Aave's vision for shared insurance pools, protocols can create bad debt backstops by pooling staked capital and shared economic security from across the ecosystem. DAOs, curators and lending markets can customize slashing triggers based on default conditions or liquidity thresholds.

* Other Structured Products:

* Downtime insurance for validators and node operators.

* MEV protection funds, where actors stake against misbehavior and get slashed for proven attacks.

#### **PoS Implementations, as in Traditional Shared Security**

The most familiar application of Universal Staking. It brings PoS-style security to specific infrastructure components, allowing shared security to be applied at a modular level.

**Expanded Utility**

* **Interoperability protocols** (such as bridges and messaging layers): Stakers post collateral to guarantee message correctness and transaction finality across chains. Slashing enforces honest relaying.

* **Oracles:** Stake is used to guarantee accuracy or uptime for price feeds and other data. Misbehavior or failure to deliver correct data can trigger slashing. This extends to MEV-resistant oracle designs and similar integrity-critical systems.

* **Sequencers and rollups:** Rollups increasingly rely on shared sequencer and operator sets to decentralize. Universal Staking provides a pooled security layer that helps these systems bootstrap trust assumptions without needing to launch a native token or maintain an isolated validator set.

### **Conclusion**

Shared security introduced a powerful primitive. It allowed systems to align incentives and inherit trust without needing to bootstrap from scratch. By enabling networks to coordinate around pooled security, it lowered the capital barrier to decentralization and helped scale early rollups, appchains, and infrastructure layers.

Universal Staking is the natural next step. It does not replace shared security but expands its reach. By generalizing the concept beyond validator coordination, it applies the same principles to a broader set of use cases. This includes native staking, risk underwriting, insurance, MEV protection, and incentive design.

The result is a flexible and modular coordination layer. Capital, incentives, and enforcement can now be orchestrated across a wide range of applications. The same mechanism that once secured chains can now secure infrastructure, protocols, and entire ecosystems.

Symbiotic is the programmable layer that makes this possible. It enables builders to design staking flows, slashing conditions, and validator sets, while continuously enforcing the rules.

Universal Staking takes the core promise of shared security and evolves it into a universal building block for the next generation of crypto systems, now fully accessible through the Symbiotic framework.

import { Details } from "../../../components/Details";

## Relay Quickstart

This quickstart walks through the developer workflow that the repo enables: spinning up Symbiotic Core locally, preparing vaults and operators, wiring middleware, and bringing a relay-powered network online.

After completing this guide, you will learn how to:

1. Spin up Symbiotic Core locally

2. Set up test Vaults and Operators

3. Configure Your Relay-backed Network's Smart Contracts

4. Bring Your Network Online

```

symbiotic-super-sum

├─ network-scripts

│ ├─ deploy.sh

│ ├─ genesis-generator.sh

│ ├─ sidecar-start.sh

│ └─ sum-node-start.sh

├─ off-chain

│ ├─ abis/

│ ├─ cmd/

│ │ ├─ benchmark/

│ │ └─ node/

│ │ └─ main.go

│ └─ internal/

│ ├─ contracts/

│ │ └─ sumTask.go

│ └─ utils/

├─ script

│ ├─ MyRelayDeploy.sol

│ ├─ mocks/

│ ├─ my-relay-deploy.toml

│ └─ utils/

├─ src

│ ├─ SumTask.sol

│ └─ symbiotic

│ ├─ Driver.sol

│ ├─ KeyRegistry.sol

│ ├─ Settlement.sol

│ └─ VotingPowers.sol

├─ generate_network.sh

├─ package.json

└─ …

```

### Prerequisites

Make sure to have all the tools listed below installed before you start.

1. **Git** ([Installation Guide](https://git-scm.com/downloads))

2. **Foundry** - Ethereum development toolchain ([Installation Guide](https://book.getfoundry.sh/getting-started/installation))

3. **Node.js** (v18 or later) and **npm** ([Installation Guide](https://nodejs.org/en/download/))

4. **Docker** ([Installation Guide](https://docs.docker.com/get-docker/))

5. **Go** (v1.21 or later) ([Installation Guide](https://golang.org/doc/install))

6. Python (v3.11 or later) ([Installation Guide](https://www.python.org/downloads/))

### **1. Deploy Symbiotic Core and Setup Your First Vault**

#### **Deploy Symbiotic Core to your local chain**

Symbiotic Core comprises the foundational contracts that govern the Symbiotic ecosystem, offering a comprehensive suite for its administration and interaction. The repository provides pre-configured scripts to facilitate deployment to a local chain, as well as additional utilities designed to streamline ongoing workflows with the core contracts.

`SymbioticCoreInit.sol` is the integration script that spins up fresh factories, registries, vaults, and helper services, then exposes utilities for building test scenarios. `SymbioticCoreConstants.sol` is the address book library that returns the canonical contract set and supported collateral tokens for mainnet, Holešky, Sepolia, and Hoodi. `SymbioticCoreBindings.sol` contains the Foundry broadcast helpers used to create vaults, register operators/networks, manage opt-ins, and exercise slashing flows against those core contracts.

Core contracts can be deployed using `_initCore_SymbioticCore` function ([script details](https://github.com/symbioticfi/relay-contracts/blob/deploy-script-updates/script/RelayDeploy.sol#L101)):

```solidity [@symbioticfi/relay-contracts/script/deploy/RelayDeploy.sol#101]

function getCore() public withoutBroadcast loadConfig returns (SymbioticCoreConstants.Core memory) {

if (!SymbioticCoreConstants.coreSupported()) {

if (config.get("vault_factory").data.length == 0) {

SymbioticCoreConstants.Core memory core = _initCore_SymbioticCore(false); // [!code focus]

```

The console output lists every deployed Symbiotic Core contract (vault factory, registries, opt-in services, etc.). Persist these addresses—you’ll feed them into the rest of the quickstart.

#### **Deploy a vault**

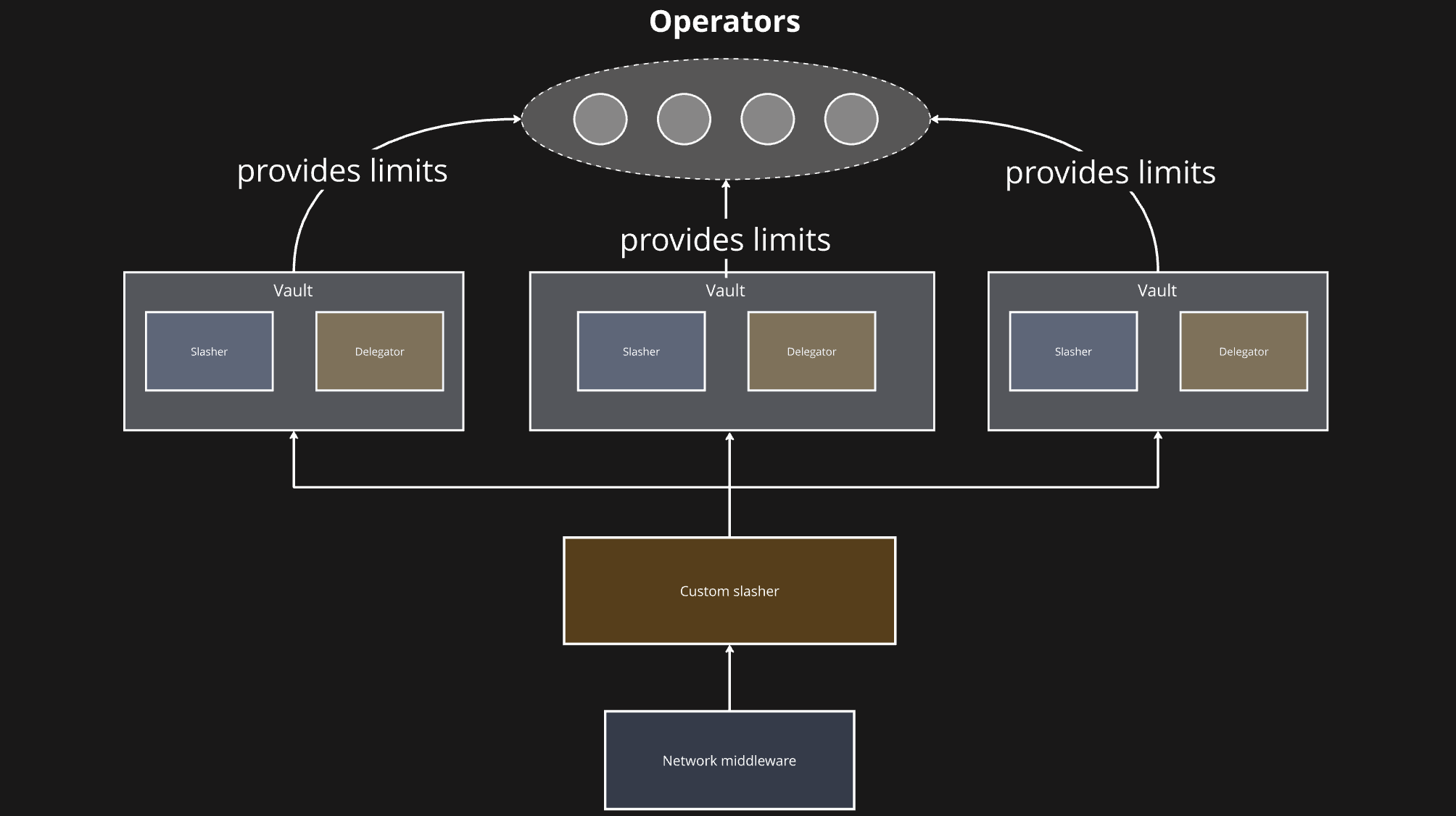

Vaults are the delegation and restaking management layer of Symbiotic. They handle three crucial parts of the Symbiotic economy: accounting, delegation strategies and slashing processing

The vault is created during operator registration by VotingPowers contract ([see contract details](https://github.com/symbioticfi/relay-contracts/blob/main/src/modules/voting-power/extensions/logic/OpNetVaultAutoDeployLogic.sol#L289)).

```solidity [@symbioticfi/relay-contracts/src/modules/voting-power/extensions/logic/OpNetVaultAutoDeployLogic.sol#289]

function createVault(

uint64 version,

address owner,

bytes memory vaultParams,

uint64 delegatorIndex,

bytes memory delegatorParams,

bool withSlasher,

uint64 slasherIndex,

bytes memory slasherParams

) public returns (address, address, address) {

return IVaultConfigurator(IOpNetVaultAutoDeploy(address(this)).VAULT_CONFIGURATOR())

.create(

IVaultConfigurator.InitParams({

version: version,

owner: owner,

vaultParams: vaultParams,

delegatorIndex: delegatorIndex,

delegatorParams: delegatorParams,

withSlasher: withSlasher,

slasherIndex: slasherIndex,

slasherParams: slasherParams

})

);

}

```

For testnet or mainnet vaults you can skip this step and create one directly via the Vault Factory UI at [https://app.symbiotic.fi/create](https://app.symbiotic.fi/create)

### **2. Opt-Ins and Stake Allocation**

#### **Required On-Chain Actions**

In Symbiotic, networks are represented through a network address (either an EOA or a contract) and a middleware contract. Deploy the network contract using the DeployNetworkBase script. During initialization, the network is also registered within NetworkRegistry ([script details](https://github.com/symbioticfi/symbiotic-super-sum/blob/5e7625c8fb16acdd30a7695050f2f7b5c8f44d32/script/MyRelayDeploy.sol#L101)).

```solidity [script/MyRelayDeploy.sol#101]

function getNetwork() public withoutBroadcast loadConfig returns (address) {

if (config.get("network").data.length == 0) {

address[] memory proposersAndExecutors = new address[](1);

proposersAndExecutors[0] = getDeployerAddress();

SymbioticCoreConstants.Core memory core = getCore();

vm.broadcast();

address networkImpl =

address(new Network(address(core.networkRegistry), address(core.networkMiddlewareService)));

config.set(

"network",

_deployContract(

NETWORK_SALT,

networkImpl,

abi.encodeCall(

INetwork.initialize,

(INetwork.NetworkInitParams({

globalMinDelay: 0,

delayParams: new INetwork.DelayParams[](0),

proposers: proposersAndExecutors,

executors: proposersAndExecutors,

name: "Example Network",

metadataURI: "https://example.network",

defaultAdminRoleHolder: getDeployerAddress(),

nameUpdateRoleHolder: getDeployerAddress(),

metadataURIUpdateRoleHolder: getDeployerAddress()

}))

),

getDeployerAddress(),

false

)

);

}

return config.get("network").toAddress();

}

```

The OperatorRegistry maintains a record of all registered operators.

Operators must register here before they can participate in network activities or receive stake allocations ([script details](https://github.com/symbioticfi/symbiotic-super-sum/blob/5e7625c8fb16acdd30a7695050f2f7b5c8f44d32/script/MyRelayDeploy.sol#L371)).

```solidity [script/MyRelayDeploy.sol#371]

getCore().operatorRegistry.registerOperator();

```

Opt-ins are crucial for establishing connections between different entities in the Symbiotic ecosystem. Through the OperatorNetworkOptInService, operators can opt into networks they wish to work with. This signifies their willingness to provide services to these networks.

Operators use the OperatorVaultOptInService to opt into specific vaults. This allows them to receive stake allocations from these vaults ([script details](https://github.com/symbioticfi/symbiotic-super-sum/blob/5e7625c8fb16acdd30a7695050f2f7b5c8f44d32/script/MyRelayDeploy.sol#L372)).

```solidity [script/MyRelayDeploy.sol#372]

getCore().operatorNetworkOptInService.optIn(address(getNetwork())); // [!code focus]

votingPowers.registerOperator();

IVault vault = IVault(votingPowers.getAutoDeployedVault(operator.addr));

getCore().operatorVaultOptInService.optIn(address(vault)); // [!code focus]

```

Network opt into desired vaults by calling `setMaxNetworkLimit()` on each vault’s delegator contract ([script details](https://github.com/symbioticfi/relay-contracts/blob/70dc1ae21bdebf08e2f01246a42e31aee6a1c39d/src/modules/voting-power/extensions/OpNetVaultAutoDeploy.sol#L69)).

```solidity [@symbioticfi/relay-contracts/src/modules/voting-power/extensions/OpNetVaultAutoDeploy.sol#69]

(address vault, address delegator,) = OpNetVaultAutoDeployLogic.createVault(operator);

_registerOperatorVault(operator, vault);

if (isSetMaxNetworkLimitHookEnabled()) {

ISetMaxNetworkLimitHook(NETWORK())

.setMaxNetworkLimit(delegator, SUBNETWORK_IDENTIFIER(), type(uint256).max); // [!code focus]

}

```

### **3. Network Middleware**

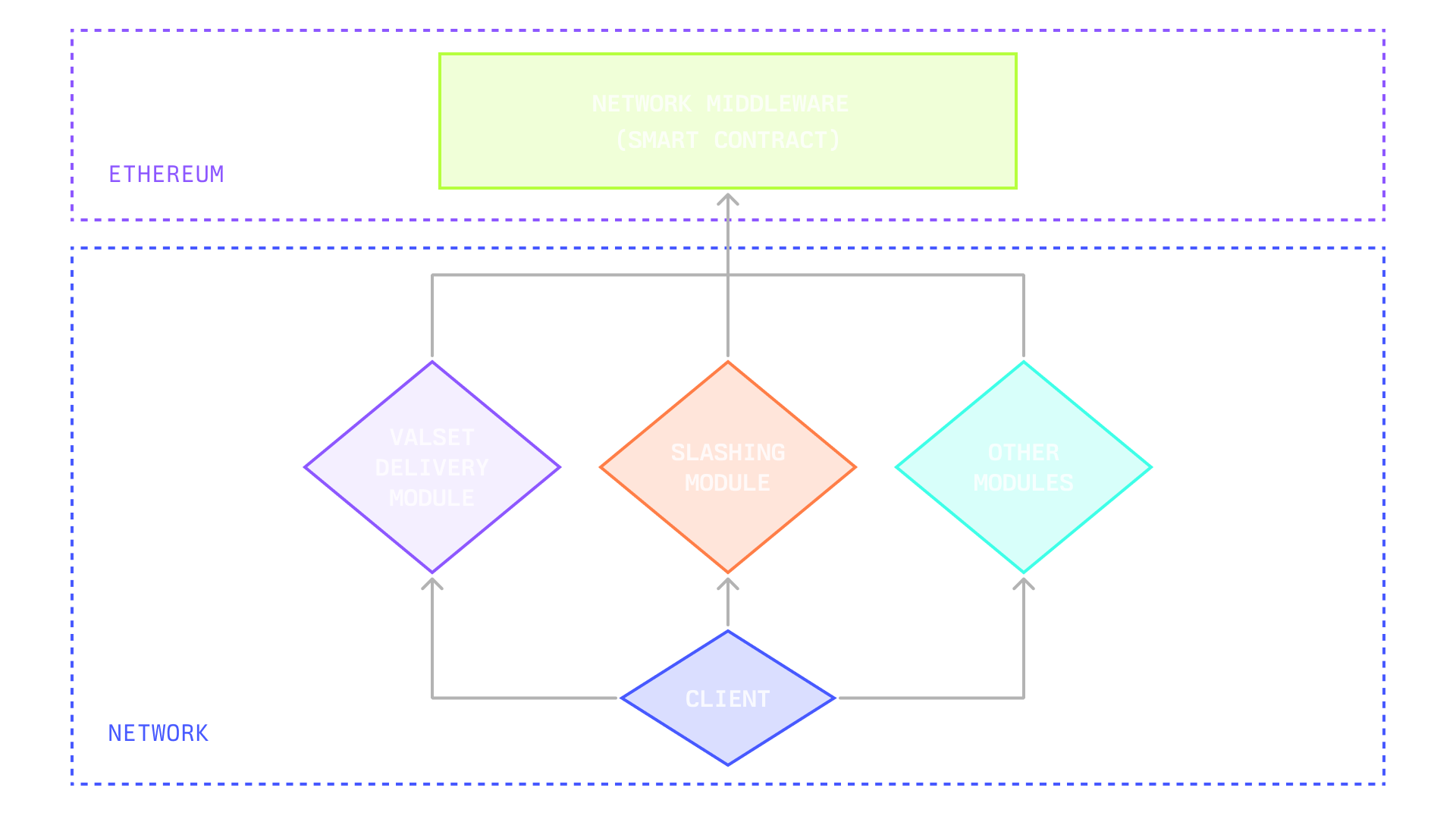

#### **Overview**

Relay Contracts use a modular architecture with five core modules that together manage validator networks, ensuring flexibility and clear separation of concerns.

* **Network** integrates Relay Contracts into the Symbiotic ecosystem, providing verifiable delays, standardized lifecycle management, and serving as the network address across the system.

* **VotingPowerProvider** connects to Symbiotic Core to calculate operator and vault voting power based on stake and rules. It supports extensible strategies for onboarding, slashing, rewards, and key management.

* **KeyRegistry** manages and verifies operators’ cryptographic keys (BLS BN254, ECDSA SECP256K1), supporting registration, verification, and lifecycle management.

* **ValSetDriver** derives and maintains validator sets for off-chain components, managing epoch transitions and linking on-chain voting power with off-chain consensus.

* **Settlement** commits compressed validator sets each epoch, verifies signatures, and supports multi-chain deployments for cross-chain validation.

#### **Deployment tooling**

The deployment tooling is in the `@symbioticfi/relay-contracts/script/deploy/` folder. It consists of `RelayDeploy.sol` Foundry script template and `relay-deploy.sh` bash script (Relay smart contracts use external libraries, so it's not currently possible to use solely Foundry script for multi-chain deployment).

* `RelayDeploy.sol` - abstract base that wires common Symbiotic Core helpers and exposes the four deployment hooks: KeyRegistry, VotingPowerProvider, Settlement, and ValVetDriver

* `relay-deploy.sh` - orchestrates per-contract multi-chain deployments

The script deploys Relay modules under [OpenZeppelin's TransparentUpgradeableProxy](https://github.com/OpenZeppelin/openzeppelin-contracts/blob/master/contracts/proxy/transparent/TransparentUpgradeableProxy.sol) using [CreateX](https://github.com/pcaversaccio/createx) (it provides better control for production deployments and more simplified approaches for development).

#### **Deployment**

1. Implement your `MyRelayDeploy.sol` Foundry script with the deployment configuration of your Relay modules:

* Implement all virtual functions of `RelayDeploy.sol`

* In the constructor, take the path of the `toml` file

* Use additional helpers such as `getCore()`, `getKeyRegistry()`, `getVotingPowerProvider()`, etc. (see full list in [RelayDeploy.sol](https://github.com/symbioticfi/relay-contracts/blob/deploy-script-updates/script/RelayDeploy.sol))

2. Implement your `my-relay-deploy.toml` configuration file with RPC URLs needed for deployment and specify which modules to deploy on which chains

3. Execute the deployment script, e.g.:

```bash

./lib/relay-contracts-new/script/deploy/relay-deploy.sh ./script/MyRelayDeploy.sol "$DEPLOY_CONFIG_PATH" --broadcast --private-key 0xac0974bec39a17e36ba4a6b4d238ff944bacb478cbed5efcae784d7bf4f2ff80

```

At the end, your `toml` file will contain the addresses of the deployed Relay modules.

#### Middleware contract

Networks need a middleware contract that incorporates custom logic and must include slashing logic.

The script sets middleware for the network in the following way ([script details](https://github.com/symbioticfi/symbiotic-super-sum/blob/5e7625c8fb16acdd30a7695050f2f7b5c8f44d32/script/MyRelayDeploy.sol#L291))

```solidity [script/MyRelayDeploy.sol#291]

Network(payable(network))

.execute(

address(core.networkMiddlewareService),

0,

abi.encodeWithSelector(INetworkMiddlewareService.setMiddleware.selector, votingPowerProvider),

bytes32(0),

bytes32(0)

);

```

### **4. Network Go Live**

The Symbiotic Relay is a peer-to-peer sidecar network that runs alongside main blockchain nodes using a stateless design based entirely on on-chain state. A built-in HTTP API allows querying validator data, tracking epochs, and managing quorum signature aggregation.

Symbiotic-super-sum spins up a mini Symbiotic relay network on your laptop: two local blockchains, a contract deployer, and as many operator nodes as you request. Once the contracts are live, a small genesis job hands every relay node the same starting snapshot so they agree on history. Each operator runs a relay sidecar that keeps them chatting over libp2p, watches both blockchains, and exposes a simple API. A matching sum node sits beside each relay, grabs the contract addresses, and handles the actual task submissions or aggregation work. Together, these containers mimic the full relay network

#### **Running network**

`generate_network.sh` generates Docker configuration. Start the network by running `docker compose --project-directory temp-network up -d`

There are several implementations of relay client - [ts](https://github.com/symbioticfi/relay-client-ts), [rust](https://github.com/symbioticfi/relay-client-rs) and [go](https://github.com/symbioticfi/relay).

Here is Go example of integration to sidecar network ([script details](https://github.com/symbioticfi/symbiotic-super-sum/blob/5e7625c8fb16acdd30a7695050f2f7b5c8f44d32/off-chain/cmd/node/main.go#L315)):

```go [off-chain/cmd/node/main.go#315]

relayClient = v1.NewSymbioticClient(conn)

...

suggestedEpoch := uint64(0)

epochInfos, err := relayClient.GetLastAllCommitted(ctx, &v1.GetLastAllCommittedRequest{}) // [!code focus]

if err != nil {

return err

} else {

for _, info := range epochInfos.EpochInfos {

if suggestedEpoch == 0 || info.GetLastCommittedEpoch() < suggestedEpoch {

suggestedEpoch = info.GetLastCommittedEpoch()

}

}

}

resp, err := relayClient.SignMessage(ctx, &v1.SignMessageRequest{ // [!code focus]

KeyTag: 15,

Message: msg,

RequiredEpoch: &suggestedEpoch,

})

if err != nil {

return err

}

```

Another example for cosmos-sdk can be found [here](https://github.com/symbioticfi/cosmos-relay-sdk).

## **Secure Attestations**

Secure attestations are **stake-backed signatures over a message hash** that contracts can verify against the active validator set header.

Concretely:

* The **validator set** for epoch `e` is fixed by a committed header (operators, keys, weights, threshold).

* Operators in that set sign a **message hash**.

* An aggregator combines these signatures into an aggregate proof.

* A **Settlement** contract on the destination chain verifies the proof against the header for epoch `e`.

### Message Contents (typical)

The protocol doesn’t hardcode a single message struct, but in practice you want something like:

* `networkId` – Relay network identifier

* `subnetworkId` – optional, for partitioned logic

* `epoch` or `valsetId` – which validator set header must be used

* `payloadType` – enum or tag (bridge, checkpoint, oracle, etc.)

* `payloadHash` – hash of the actual data your app cares about

* `dstChainId` – EVM chain where this will be verified

* `dstApp` or `dstContract` – target contract / app identifier

* `expiry` – timestamp or block after which the attestation is invalid

* `nonce` – monotonically increasing per channel / app

You encode this structure, compute `messageHash = keccak256(encodedMessage)`, and **only `messageHash` is signed** by operators.

### Aggregation and Verification

The flow is:

1. **Build the message**

Middleware or the app constructs the message struct, fills `epoch`, `dstChainId`, `dstApp`, `nonce`, `expiry`, etc., and computes `messageHash`.

2. **Operators sign**

Each operator in the **current validator set for `epoch`** signs `messageHash` with its registered key (BLS or ECDSA, depending on your Relay config).

3. **Aggregate off-chain**

An aggregator collects signatures and:

* for the **Simple** path:

* aggregates BLS signatures into `sigmaAgg`

* builds a participant bitmap / list

* for the **ZK** path:

* uses the individual signatures and weights to generate a zk proof that “signers’ voting power ≥ threshold for header H and messageHash M”

4. **Submit to Settlement**

On the destination chain, the aggregator (or any relayer) calls something like:

* `settlement.verifyAndConsume(message, epoch, sigmaAgg, participants)` for Simple, or

* `settlement.verifyAndConsume(message, epoch, zkProof)` for ZK.

5. **On-chain check**

Settlement:

* loads the **validator set header** for `epoch`

* reconstructs keys and weights from that header

* runs either:

* **SimpleVerifier**: check BLS aggregate against the participants and ensure their summed voting power ≥ threshold

* **ZKVerifier**: check the proof that encodes both signature validity and power ≥ threshold

If verification passes, your app logic (bridge, rollup, oracle, etc.) is allowed to execute.

### Safety Properties

Secure attestations are tied down in a few specific ways:

* **Bound to a validator set**

The message includes `epoch` (or a valset ID). Settlement only verifies against the header stored for that epoch. An attestation for epoch `e` cannot be validated against the header for epoch `e+1`.

* **Bound to destination**

`dstChainId` and `dstApp` are part of the signed payload. The same hash cannot be replayed on a different chain or different contract because the signature is over the full encoded message.

* **Replay protection**

Your app (or Settlement integration) tracks:

* `nonce`: reject messages with a nonce ≤ lastSeenNonce for that channel / app

* `expiry`: reject messages whose expiry is in the past

* **Slashable misbehavior**

If operators sign:

* two different payloads for the same `(networkId, subnetworkId, epoch, nonce)`

* or obviously invalid content (e.g. violates your protocol’s invariants),

that evidence can be fed into your Network’s middleware, which then submits a **slashing

request** to the relevant vaults in Symbiotic. The economic backing for those keys is what

makes the attestation “secure”.

So in short: a secure attestation is a message bound to a specific epoch, network, and destination, proven on-chain to have signatures from enough stake-weighted operators in that epoch’s validator set.

## **Settlement**

Settlement is the on-chain endpoint for Relay. It stores validator set headers (operators, keys, weights, thresholds) per network / subnetwork / epoch and verifies aggregated signatures (attestations) against those headers on the chains where apps live. Applications don’t talk to `VotingPowerProvider` or `ValSetDriver` directly; they call Settlement to check whether enough of the current validator set signed a given message.

#### Contract responsibilities

Settlement instances (one per Relay network per chain) are responsible for:

* **Committing headers**

Accept compressed validator set headers (for example, once per epoch) and store them keyed by `(network, subnetwork, epoch)`.

* **Verifying attestations**

Given:

* a message (or hash)

* an epoch / header ID

* an aggregate signature or zk proof

Verifier checks:

* the proof matches the message

* the participating validators’ total voting power is at least the threshold from the header

If both hold, it returns success so the calling app can continue.

#### Multi-chain

The same validator set can secure multiple chains. Each chain runs its own Settlement instance, and the Relay committer posts the same header to all replicas. Applications on different chains therefore verify against identical validator sets and thresholds for a given epoch, even though verification is performed locally on each chain.

#### Cost model (intuition)

Costs stay near-flat in validator set size. Header updates are small, infrequent writes because a compressed header is stored once per epoch. Verifying an attestation requires a single aggregate check: with the Simple verifier this is one BLS aggregate pairing plus summing the listed signers’ weights, while with the ZK verifier it is one zkSNARK verification where the signer set and weight check are already encoded in the proof. You pay per attestation, not per validator.

#### Failures

Verification fails (returns false / reverts) if:

* the referenced epoch or header is not committed or does not match the network

* the proof is invalid or does not match the message hash

* the signing validators’ total voting power is below the threshold

In all of these cases, the application must not execute the gated action (no unlock, no finalize, no state update).

## **Valset (Validator Set)**

The **validator set** is the current list of operators and their weights that a network uses for signing and verification during a given epoch. In Relay, this is represented by a **validator set header** that ValSetDriver helps derive and then commit to the Settlement contracts.

At any moment in an epoch, the validator set answers three questions:

* which operators are active

* which keys they use to sign

* how much **voting power** each one has (as computed by the VotingPowerProvider)

Applications and Settlement never recompute this themselves – they read the committed header and verify signatures against it.

### Epoch Formation

`ValSetDriver` is the on-chain “driver” the Relay binary uses to derive validator sets epoch by epoch. At the start of each network epoch (or whenever the network decides to rotate), the off-chain Relay nodes:

1. **Discover eligible operators**

* Read operator/vault relationships and voting power from `VotingPowerProvider`.

* Respect onboarding modules (whitelist/blacklist/jail, shared vs operator vaults, multi-token rules) so only **registered and permitted** operators are considered.

* Filter to operators that have opted into the network and meet minimum power / inclusion constraints configured in `VotingPowerProvider`.

2. **Select active key material**

* Fetch cryptographic keys for these operators from `KeyRegistry` (BLS BN254 or ECDSA secp256k1).

* Enforce key requirements: tags, key types, and quorum / threshold rules as configured via `ValSetDriver`.

3. **Assign weights**

* Call `VotingPowerProvider` to get each operator’s **voting power** for this network (stake → power, token weights, vault weights, etc.).

* Apply any network-side caps (e.g. max power per operator, max validator count) that `ValSetDriver` exposes for Relay config.

4. **Fix the decision threshold**

* Choose a decision rule like `> 50%` or `≥ 2/3` of total voting power.

* Encode this into the header metadata so `Settlement` and applications know what constitutes a valid quorum for verification.

5. **Produce a compact header**

* Compress: operator IDs, keys (or key hashes), weights, epoch number, network id, and the chosen threshold into a **ValSetHeader**.

* Compute a `headerHash = keccak256(abi.encode(header))` (conceptually – exact struct is handled inside the contracts).

This header is what gets committed on-chain and later used by `Settlement` and apps to verify aggregated signatures.

### Storage and Rotation

`ValSetDriver` and `Settlement` together manage **storage and rotation** of validator sets:

* **Epoch-based rotation**

* `ValSetDriver` tracks **epoch timing** and exposes the current epoch start / duration to Relay nodes.

* At each epoch boundary, Relay derives a new validator set and sends its header to the Settlement contracts.

* **On-chain storage**

* Settlement stores the current header (and usually some history) in **compressed form**, keyed by epoch or sequence.

* The driver and Settlement together act as the on-chain source of truth: “for epoch N, these are the validators, weights, and threshold”.

* **Design constraint**

* Network epochs should be long enough that the whole path

“observe stake → compute voting power → derive set → aggregate signatures → post header”

reliably fits inside the epoch window, otherwise headers risk arriving late.

### Cross-chain Commitment

Relay is designed to support **multiple chains** from a single validator set.

* `ValSetDriver` holds configuration for:

* which `Settlement` contracts (replicas) exist on which chain IDs

* verification type (Simple vs ZK) and per-replica parameters (e.g. quorum thresholds, gas-oriented constraints)

* For each epoch, the Relay binary:

* derives one validator set header

* commits that same header to all configured Settlement replicas

Applications on any of those chains read the **same header**, so verification of a given message is consistent everywhere.

### Enforcement and Verification

Once a header is committed, it becomes the **reference set** for signature checks until the next epoch’s header replaces it.

* **Verification contracts**

* Settlement uses either `SimpleVerifier` (compressed full set verification, good up to \~125 validators) or `ZKVerifier` (zkSNARK-based proof) to check that an aggregated signature meets the threshold for the committed set.

* **Enforcement properties**

* If a signature is produced using a key that is **not in the header**, verification fails – the key has no registered voting power for that epoch.

* If the aggregated signature does not correspond to a subset of validators whose **total voting power ≥ threshold**, verification fails.

* If a malicious or misconfigured app tries to verify against an old header, it will only succeed if that header is still the one committed for the relevant epoch / sequence.

From the network’s perspective, that means:

* you get deterministic, epoch-by-epoch validator sets derived from Symbiotic stake and operator status

* anyone on any connected chain can cheaply verify that “this message was signed by enough power in the active set for epoch N” using only the committed header and the verifier contracts.

So, if **VotingPowerProvider** defines *how much* power each operator has, **ValSetDriver + Settlement** define *which set* is active at a given time and enforce that only that set – with its weights and threshold – can authorize decisions.

## **Voting Power**

The `VotingPowerProvider` is the Relay contract that turns **delegated Symbiotic stake** into **operator voting power** inside a validator set. It sits between Symbiotic Core (vaults, operators, networks) and the Relay settlement layer, and exposes a clean interface for:

* which operators are in the validator set

* how much voting power each one has

* what that power was at a specific timestamp (for verifying old decisions)

This is what Relay uses to build validator sets and what Settlement uses to verify signatures.

#### Inputs

At a high level, VotingPowerProvider pulls three kinds of data:

* **Stake and vault state** from Symbiotic Core (how much collateral each operator has in which vaults / networks).

* **Onboarding / filtering modules**, e.g.

* OperatorsWhitelist / OperatorsBlacklist / OperatorsJail – which operators are even allowed in the set

* SharedVaults / OperatorVaults – which vaults are considered for this network

* MultiToken / OpNetVaultAutoDeploy – which tokens and “auto-created” vaults are in scope

* **Voting power calculators**, which define how raw stake → voting power.

The public view methods (like `getOperatorVotingPower` and `getOperatorVotingPowerAt`) are what off-chain tooling and Relay’s `ValSetDriver` actually call when they derive the active set and its weights.

### From Delegated Stake to Voting Power

The core idea: **delegated stake is the input**, but the contract lets you pick the function that maps “stake” to “voting power”.

Some standard derivations:

* **Equal** – every opted-in operator gets the same power, regardless of stake. Useful for “one node, one vote” or PoA-style governance.

* **Linear** – power proportional to stake. This is the vanilla PoS model: double the effective stake, double the voting power.

* **Capped / concave** – diminishing returns at higher stake. You can cap per-operator power or use a concave function to stop one operator from dominating the set even if they bring a lot of collateral.

* **Behavior-aware** – adjust weights based on uptime, freshness, or custom performance metrics. In practice you’d compute a “score” off-chain and feed it in via weights or parameters that sit on top of the base calculators.

`VotingPowerProvider` achieves this through a plug-in set of **VotingPowerCalculators**. The repo ships with several that you can compose or chain:

* `EqualStakeVPCalc`

* `NormalizedTokenDecimalsVPCalc` – normalize all tokens to 18 decimals

* `PricedTokensChainlinkVPCalc` – convert different tokens to a common value using Chainlink price feeds

* `WeightedTokensVPCalc` – apply token-level weights

* `WeightedVaultsVPCalc` – apply vault-level weights (e.g. “this vault counts 1.2×, that one 0.8×”)

Networks can pick a simple single calculator (e.g. “linear stake using normalized decimals”) or a pipeline (“normalize decimals → price everything in ETH → apply vault weights”).

### Multi-Token Considerations

In practice, stake can come from multiple collaterals across several vaults:

* LST A, LRT B, native token, etc.

* different decimals and potentially different prices

`VotingPowerProvider` does **not** impose one global rule here; it just provides building blocks. The network defines:

* which tokens are accepted (via MultiToken module and supported-token registration)

* how each token is converted into a single comparable number (e.g. price feeds, fixed haircuts, or simple 1:1)

* whether some tokens or vaults get higher or lower weight in the final voting power

The end result is a single voting power number per operator that already bakes in all these decisions.

### Quorum and Time Variation

Once voting power is defined, the network can reason about **quorums** and **thresholds**:

* decisions might require > 50% or ≥ 2/3 of total voting power

* some sub-protocols (e.g. light client, DA, bridge) can have their own minimum voting power requirements

Voting power is **time-varying**:

* stake moves in and out of vaults

* operators join, leave, or are jailed / unregistered

* token prices change if you use price-based calculators

* off-chain behavior metrics change over time

To keep things tractable, most networks **update the validator set once per epoch** and use that snapshot for all decisions in that period. Relay’s contracts are built around this:

* `ValSetDriver` uses `VotingPowerProvider` to derive the validator set at a chosen genesis and at subsequent epochs.

* `Settlement` verifies signatures against exactly that compressed validator set header, so verifiers and networks agree on which power distribution applied.

This gives you a clean, epoch-by-epoch history of “who had how much power when”.

### With and Without Relay

You can think of `VotingPowerProvider` as the **Relay version** of what a custom middleware might do.

* **Without Relay**

Your own middleware reads vault accounting and Delegator state directly from Symbiotic Core, applies your stake → voting power rules off-chain, and uses that to drive your protocol. You still need to handle cross-chain verification and efficient proof formats yourself.

* **With Relay**

`VotingPowerProvider` is the on-chain oracle of voting power for the Relay network. Relay’s off-chain sidecar and ValSetDriver:

* read operator/vault data from Symbiotic Core

* call `VotingPowerProvider` to get per-operator voting power

* compress that into a validator set header

* commit it into `Settlement`, which is then used to verify aggregated signatures on any connected chain

In other words: `VotingPowerProvider` is where you **define what “power” means** for your network, and Relay takes that definition and turns it into a cheap, verifiable validator set you can reuse everywhere.

## **Epochs and Delays**

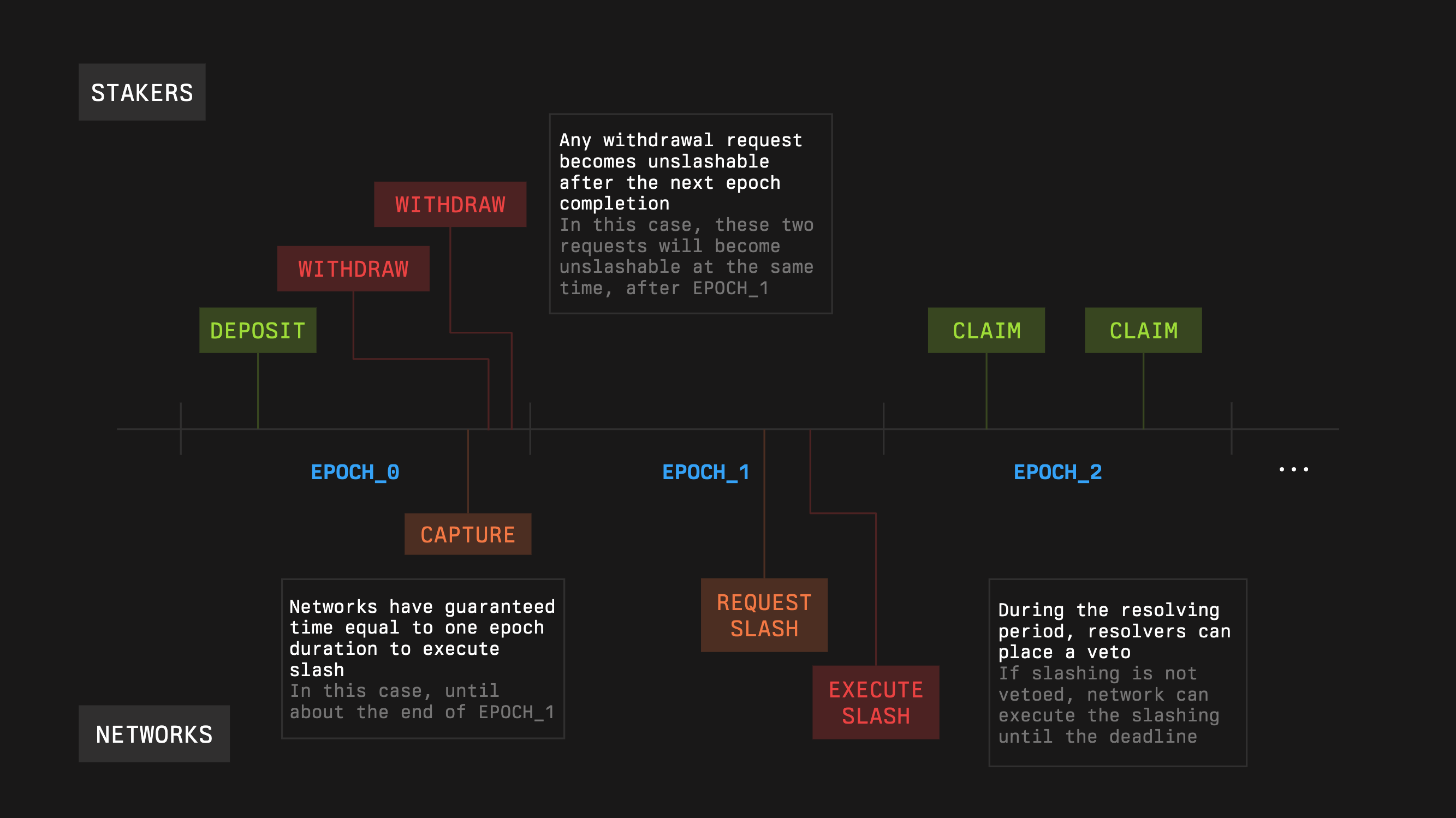

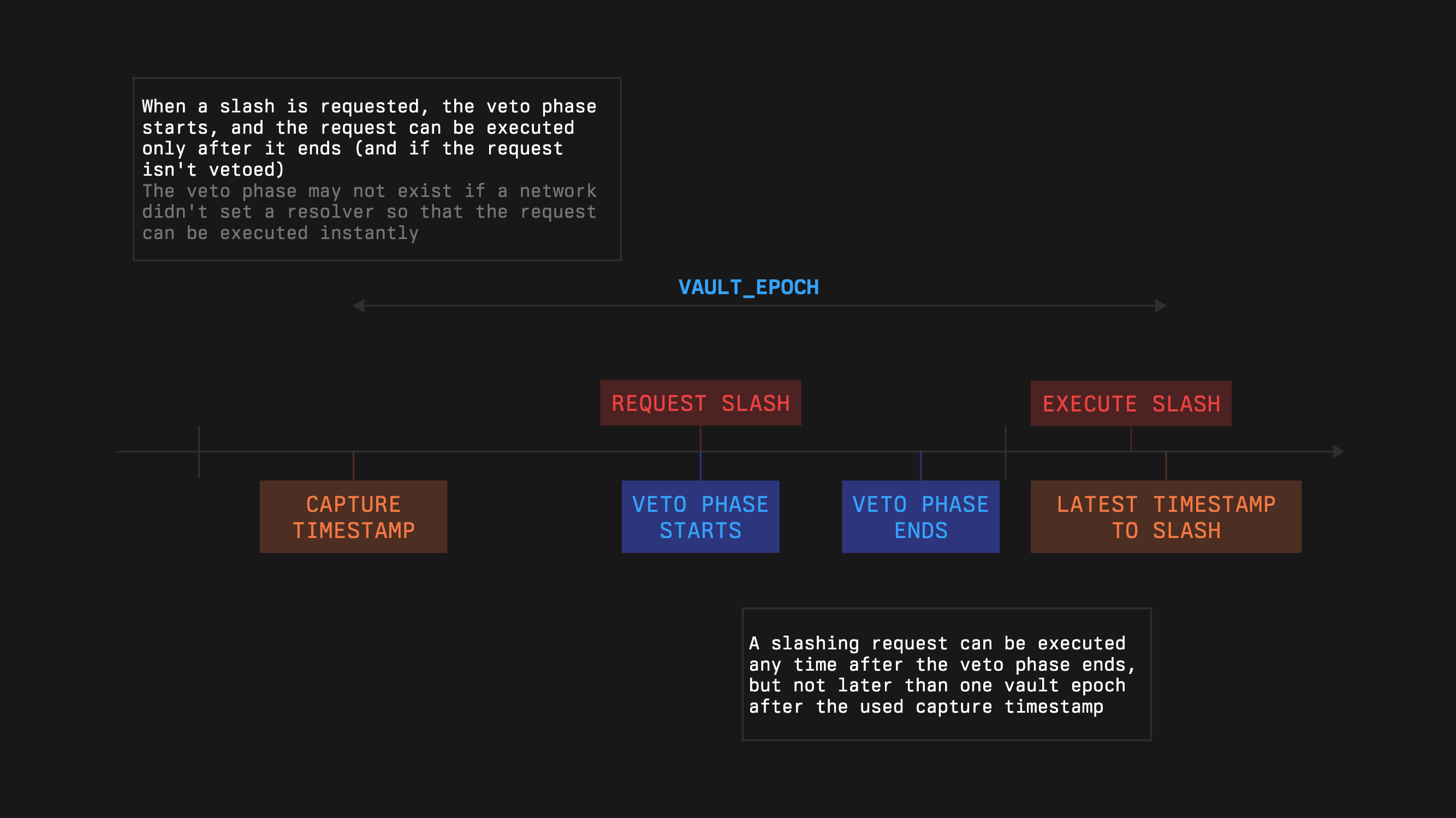

Epochs are the time rules of Symbiotic. They tell you when validator sets update, when withdrawal requests can be claimed, and how long captured guarantees stay slashable. Grouping changes at epoch boundaries keeps the stake that networks rely on stable and easy to verify.

### Vault Epochs

Each vault has an **epoch duration** set at deployment (`epochDuration`). All epochs for that vault:

* are consecutive and equal length

* use the same duration unless the curator later increases it

Vault epochs drive two things:

1. When queued withdrawals become claimable

2. The maximum look-back window for slashing previously captured guarantees

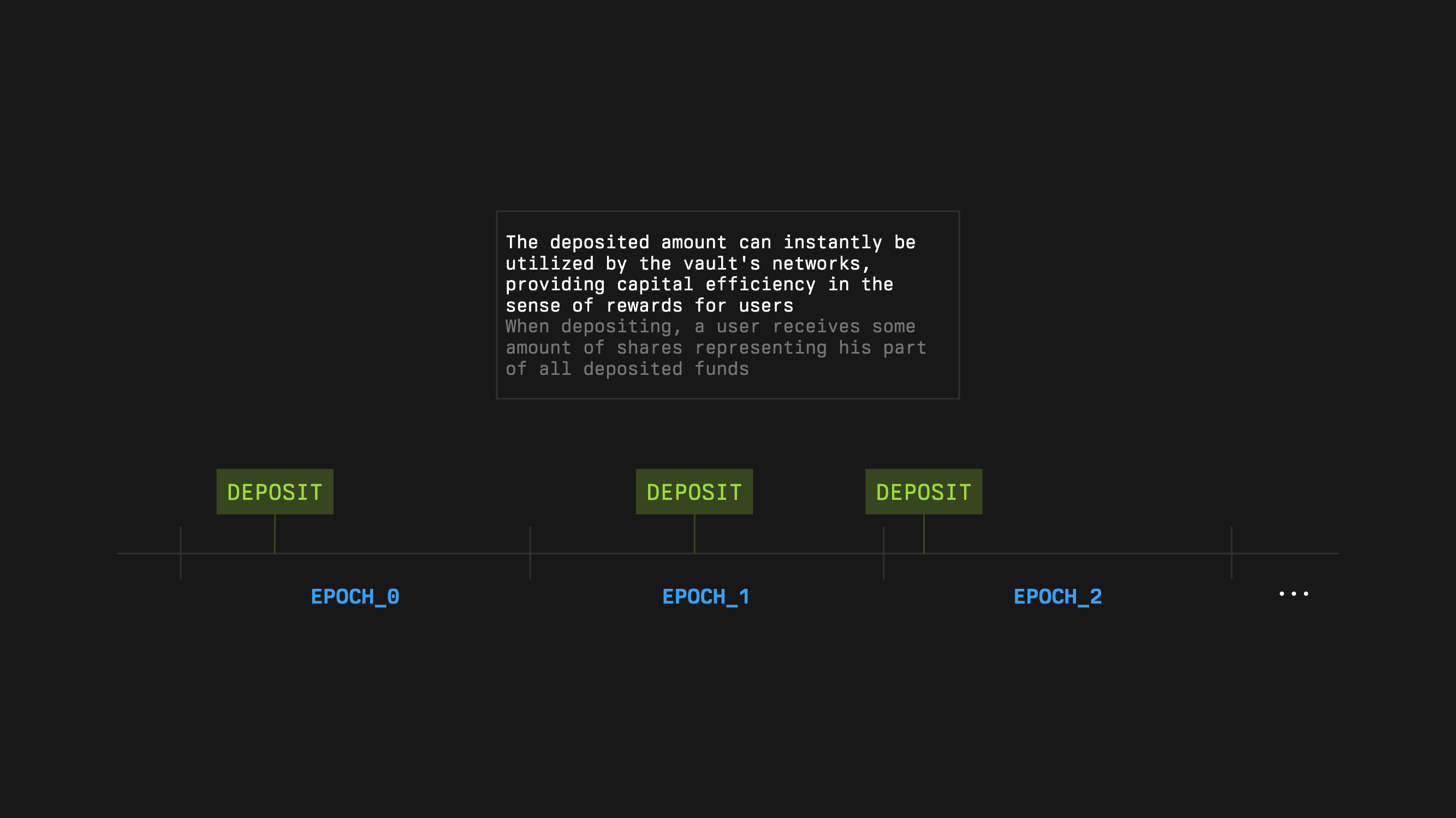

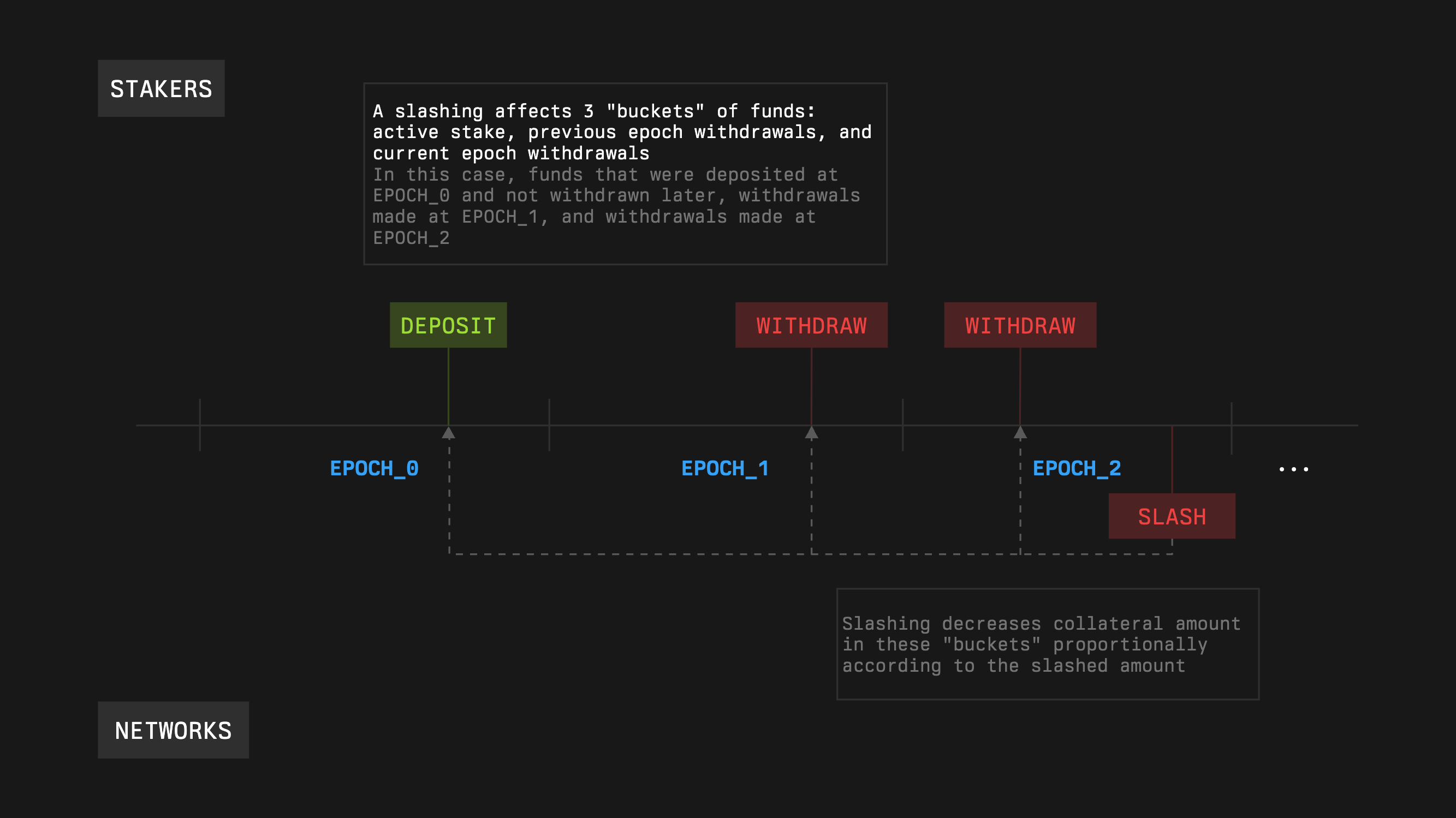

#### Withdrawal Timing

Withdrawals are a two-step, epoch-based process.

* A user submits a withdrawal request at time `t` inside epoch `k`.

* The request becomes claimable **after epoch `k+1` ends**.

If the epoch length is `E`:

* the effective delay from request to claim is in `[E, 2E)` depending on when in the epoch the user requested

* until the boundary at the end of epoch `k+1`, the requested funds remain slashable

After that boundary, the withdrawal can be claimed and is no longer subject to new slashes.

#### Capture and Slashing Window

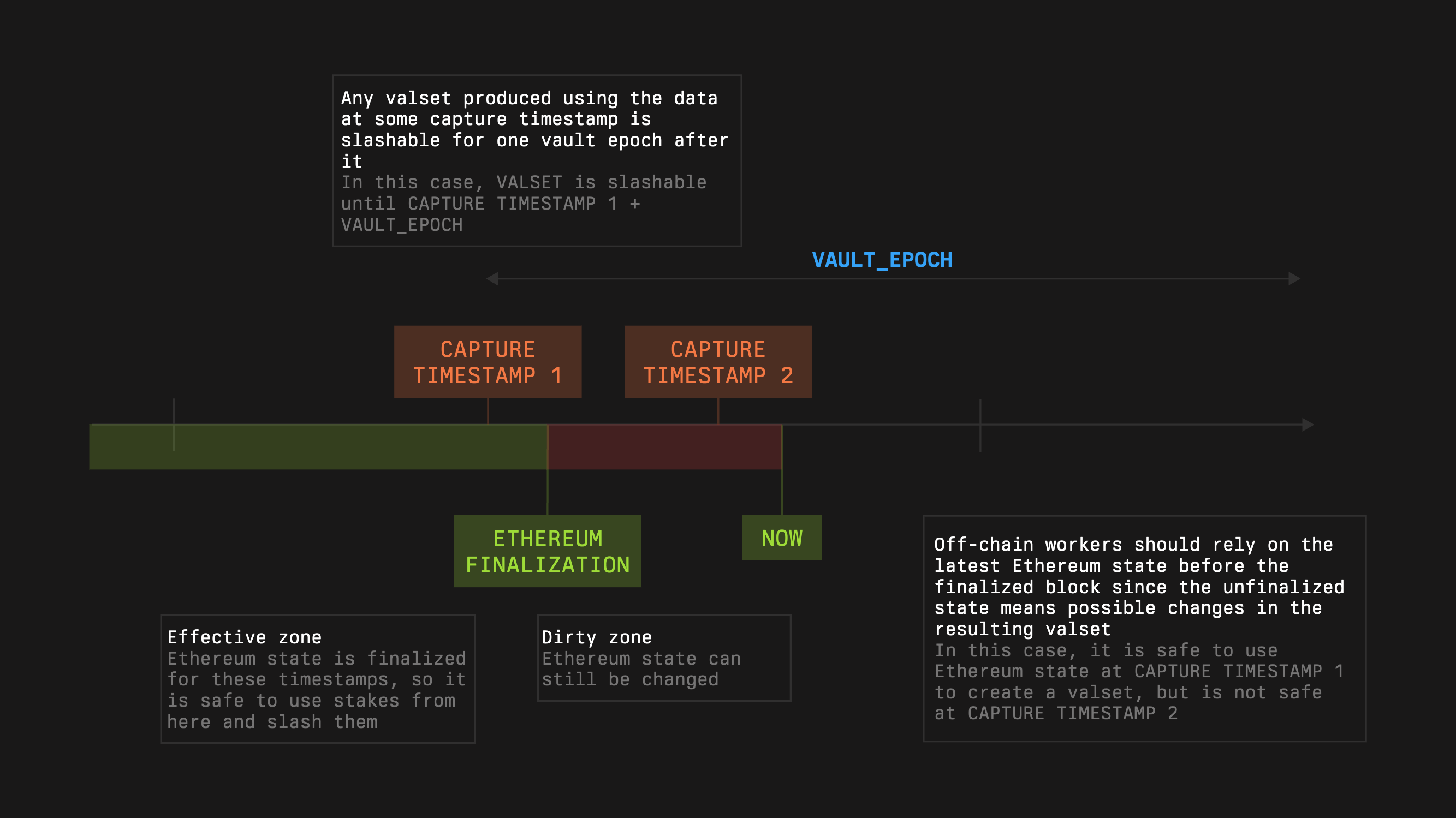

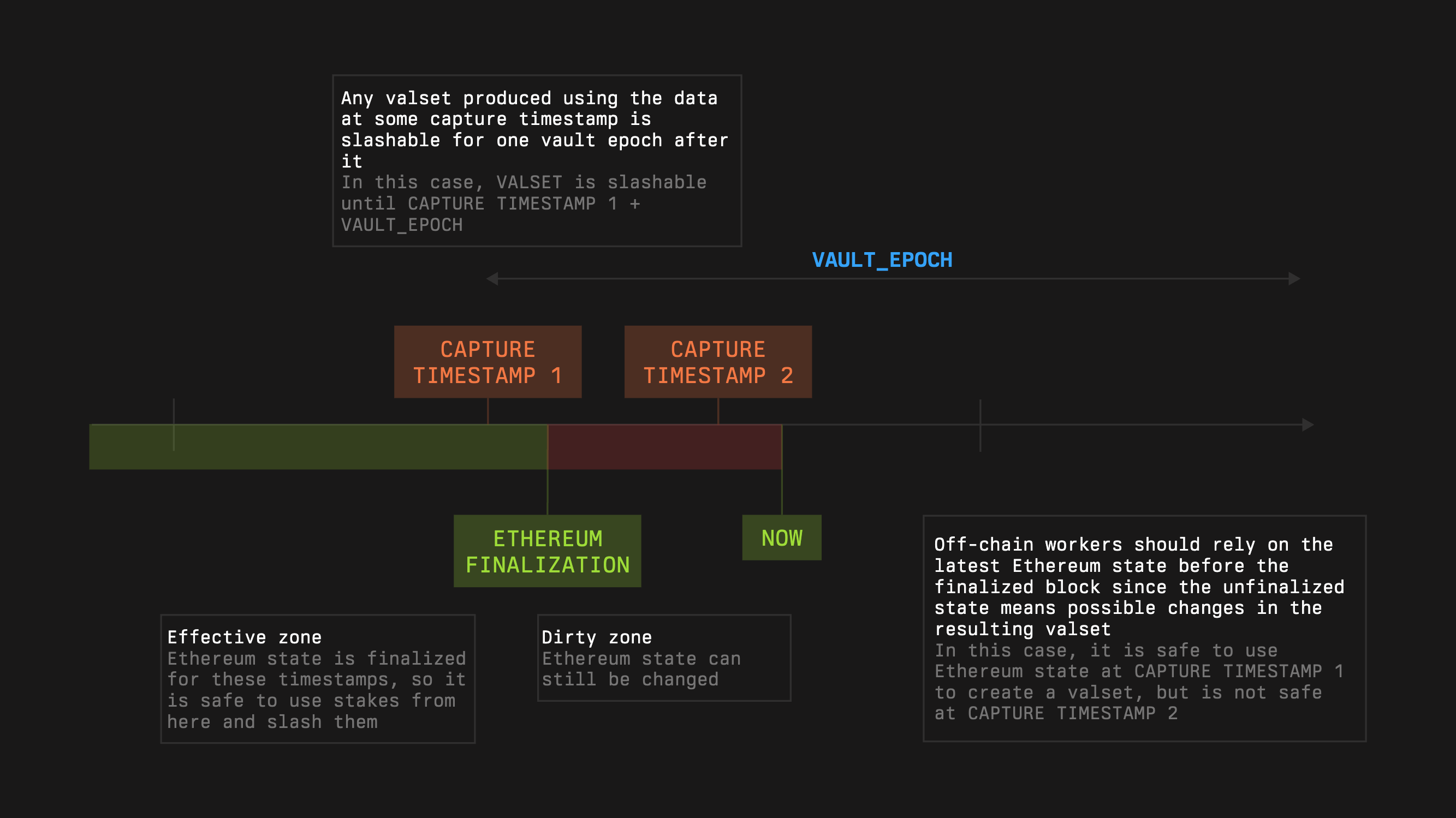

Networks do not slash against live state; they slash against **captures**.

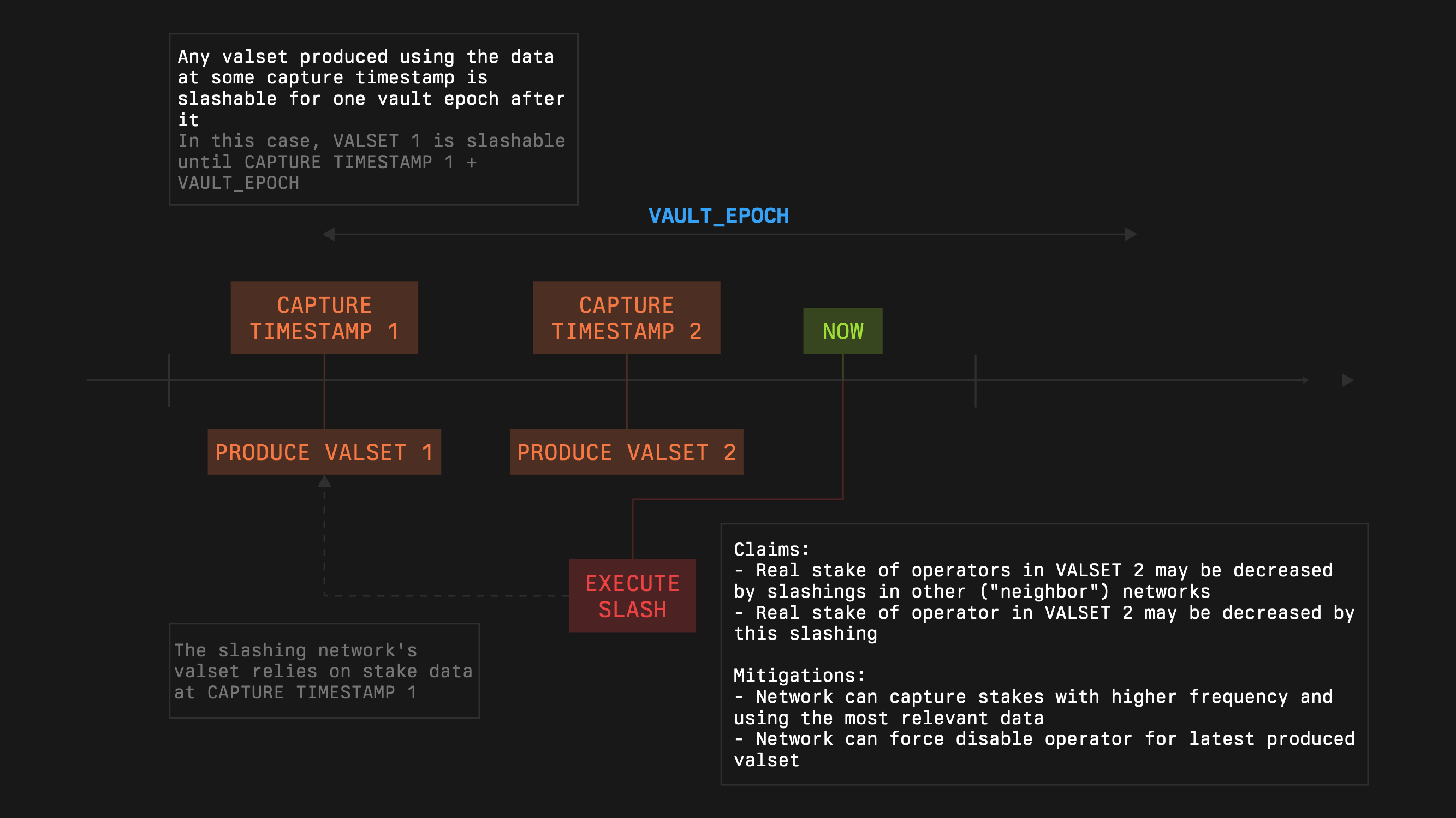

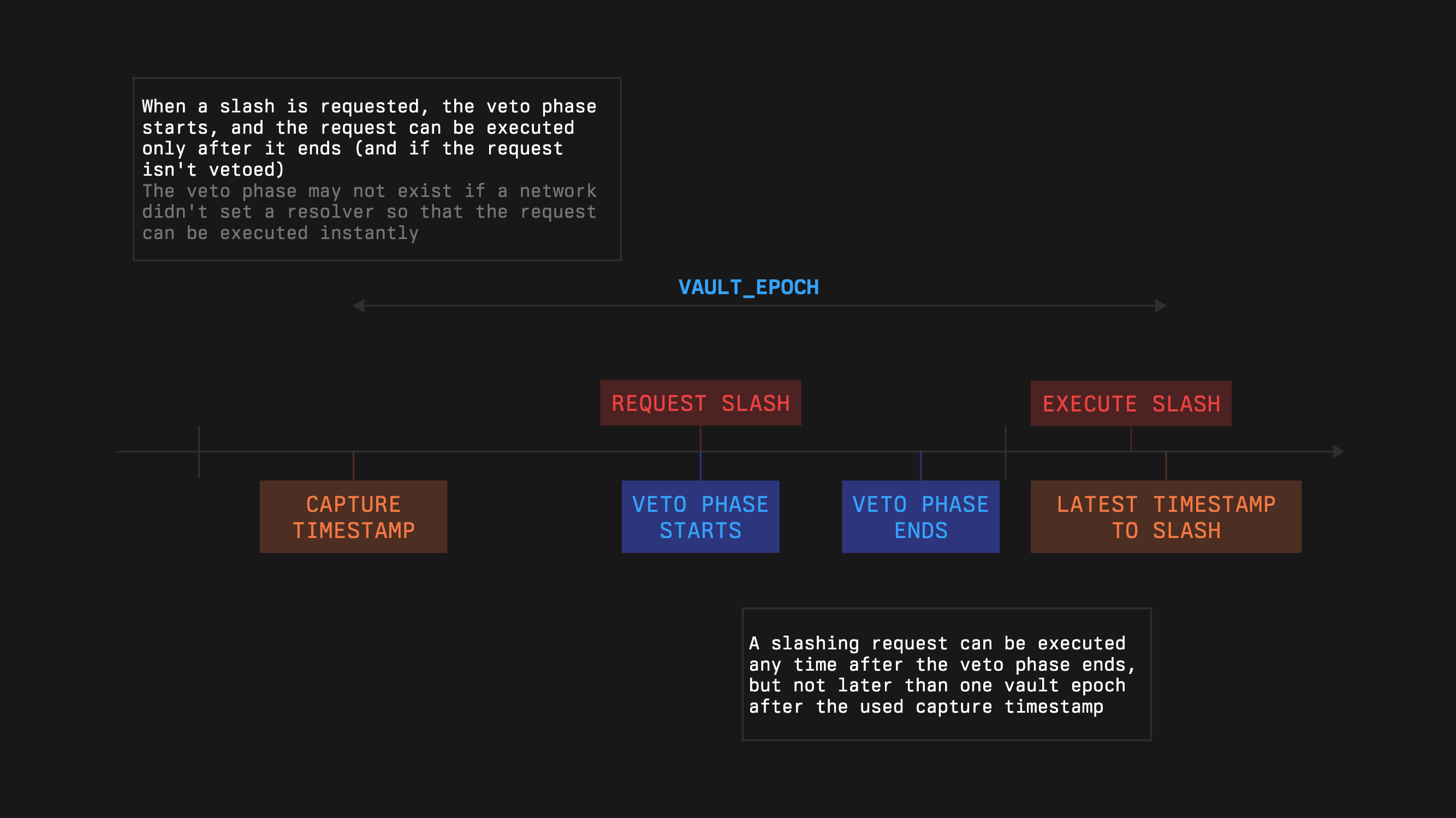

* A **captureTimestamp** is the time a Network uses to snapshot stake and validator sets.

* At capture, the Network receives a guarantee that the captured amounts remain slashable for one **vault epoch** after that timestamp.

When a slashing request is executed, the Slasher enforces:

1. **Freshness**

If the capture is older than one epoch at execution time, the request is rejected: `now − captureTimestamp ≤ vaultEpoch`

2. **Bounded amount**

Let

* `G` = guarantee captured at `captureTimestamp`

* `C` = cumulative slashes already applied for that same capture

Then any new slash must satisfy: `slashAmount ≤ G − C`

This anchors penalties to a specific snapshot and prevents double-charging or overshooting the guarantee.

### Network Epochs and Buffers

Vault epochs need to be large enough to contain the **end-to-end slashing path** for a Network.

Roughly:

`validatorSetCaptureDelay + networkEpoch + vetoWindow + executionWindow ≪ vaultEpoch`

Where:

* `validatorSetCaptureDelay` – time to produce and publish the operator set / stake snapshot

* `networkEpoch` – how often your network rotates or commits a new set

* `vetoWindow` – VetoSlasher review period, if used

* `executionWindow` – operational buffer to actually call the Slasher and finalize the transaction

If the sum approaches the vault epoch, captures risk expiring before penalties can be executed. Either shrink the network-side timings or use a vault with a longer epoch.

#### Lifecycle Notes

Epoch changes and events interact like this:

* Freshness checks use the **current** vault epoch at verification time, not the epoch duration that was in effect when the capture was taken.

* Withdrawals are slashable until the first boundary where they become claimable (end of epoch `k+1` for a request in epoch `k`).

#### Examples

**7-day vault epoch, mid-epoch withdrawal**

* `E = 7 days`.

* User requests withdrawal on day 2 of epoch `k`.

* Claim is possible right after epoch `k+1` ends → between 7 and 14 days from the request, depending on where in the epoch they requested.

* Funds remain slashable until that boundary.

**Safe timing for slashing**

* Vault epoch `E = 8 days`.

* `validatorSetCaptureDelay = 6h`, `networkEpoch = 24h`, `vetoWindow = 12h`, `executionWindow = 6h`.

* Total = 48h, well below 8 days → captures stay fresh and enforceable with plenty of margin.

## **Registries and Opt-ins**

### Registries

Registries give Networks and Operators a canonical on-chain identity that the rest of Symbiotic can reference.

#### NetworkRegistry

Stores all Networks that can receive stake, be captured, and issue slashes or rewards. A Network registers once (for example via `registerNetwork()`), then:

* can be discovered by vaults, operators, and tooling

* can be linked to its middleware, which is the only address allowed to send slashing and rewards requests on its behalf

Only registered Networks can set per-vault limits and interact with Slasher and Delegator modules.

#### OperatorRegistry

Stores all Operators (EOAs or contracts) that can receive stake and be slashed. After registering (for example via `registerOperator()`), that operator ID is used everywhere:

* opt-in services track operator–vault and operator–network opt-ins

* vault Delegators use it when returning effective stake

* slashers reference it when enforcing penalties

Unregistered operators cannot be allocated stake.

(Other registries such as token or collateral registries are used similarly: they define which assets are valid and how they are handled, but they do not change the opt-in rules.)

### Opt-ins

Opt-ins establish **consent and scope**. They define which combinations of vault, operator, and network are actually allowed to interact, so that:

* a Network can only penalize stake that was explicitly made available to it

* a vault can only allocate to operators that agreed to serve it

* an operator can only be evaluated for Networks it chose to join

This keeps slashing and rewards precise and prevents accidental penalties.

#### Opt-in surfaces

Opt-ins live at the contact points between roles:

* **Operator → Vault** via `OperatorVaultOptInService`

The operator opts into a specific vault (and can later opt out). Without this, the vault

cannot allocate stake to that operator.

* **Operator → Network** via `OperatorNetworkOptInService`

The operator opts into a Network (and its subnetworks) it is willing to serve.

* **Network → Vault** via the vault’s Delegator

The Network expresses willingness to accept stake from a vault by setting a per-vault

maximum, e.g. `setMaxNetworkLimit(subnetwork, maxStake)`.

* **Vault → Network and Operator** via Delegator configuration

The curator allocates stake by setting non-zero limits or shares for a Network and for each

operator inside that Network (for example `setNetworkLimit()`, `setOperatorNetworkLimit()`,

or `setOperatorNetworkShares()` depending on Delegator type).

**Eligibility rule**

An operator is actually eligible for stake in a given Network through a given vault only if, at the relevant timestamp:

* the operator is opted into that vault

* the operator is opted into that Network

* the Network has set a non-zero max limit for that vault

* the vault’s Delegator has a non-zero limit or share for that operator in that Network

If any of these are missing, the Delegator returns zero stake and the Slasher will reject penalties for that pair.

#### Timing and capture

Opt-ins are time-aware. All checks are evaluated at the **capture timestamp** the Network includes in its request:

* when a Network captures stake at time *T*, it receives a guarantee that the reported amounts remain slashable for one vault epoch after *T*

* when a slashing request is executed, the Slasher verifies that the capture timestamp is no older than one vault epoch and that all required opt-ins and limits were in place at that time

Opt-outs and limit changes are **forward-looking**:

* if an operator opts out today, a Network can still slash for misbehavior tied to a capture from yesterday, as long as the capture is still inside the epoch window

* new captures taken after the opt-out will see zero stake and cannot be used for future penalties

#### Lifecycle and revocation

Each participant can change its opt-ins at any time:

* operators can opt in / opt out of vaults and Networks (or invalidate signatures)

* Networks can raise or lower per-vault max limits

* curators can adjust per-network and per-operator limits and shares

These changes affect **future** captures and allocations. Previously captured guarantees remain valid until they age out of the epoch window. This prevents last-minute exits from making valid penalties impossible to execute.

### Vault access vs opt-ins

Deposit access and opt-ins are separate:

* vault-level settings such as `depositWhitelist`, `depositLimit`, and their admin roles control **who can deposit** and **how much collateral** can be active

* opt-ins and Delegator limits control **who can be allocated stake** and **who can be captured, rewarded, or slashed**

A private, allowlisted vault still requires proper opt-ins and Delegator configuration before any operator can receive stake. A public vault can accept deposits from anyone but will not actually expose those deposits to a Network or operator unless all relevant opt-ins and limits are in place.

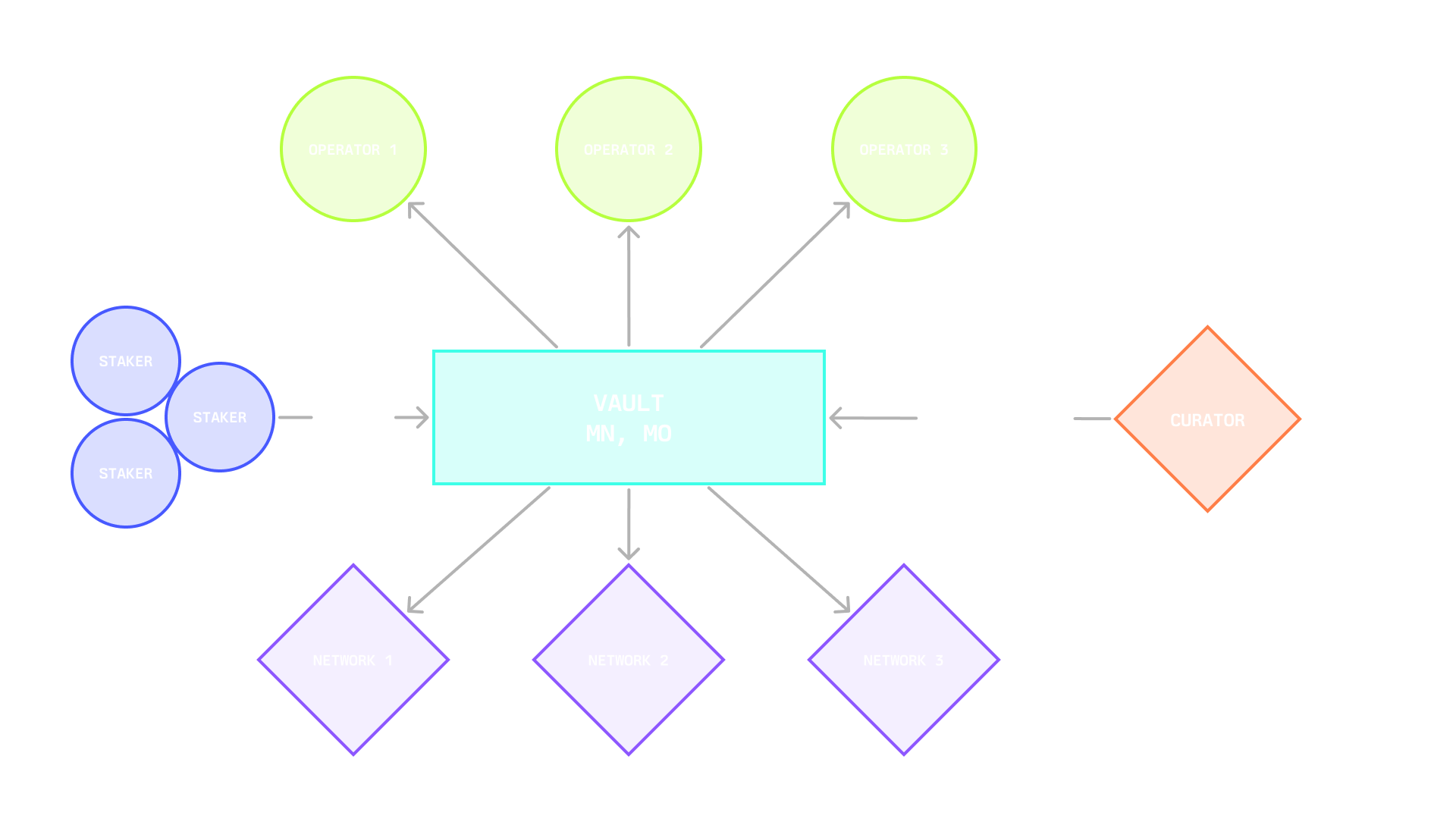

## **Curator**

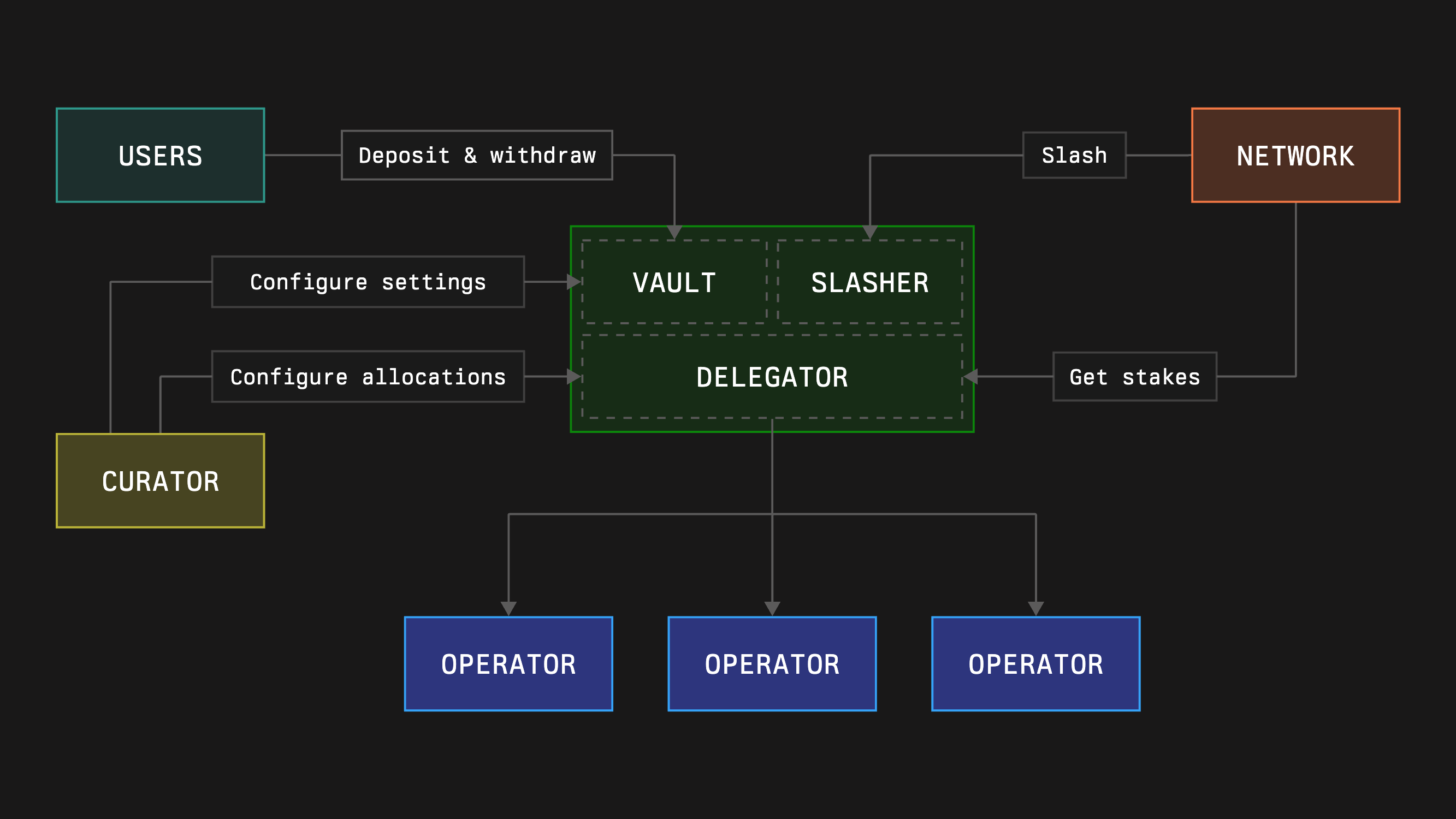

Curators set and maintain a vault’s policy. They decide how stake is spread across networks and operators, what kind of slashing flow applies, and who can deposit. Stakers choose a vault because they trust the curator’s discipline on risk, timing, and counterparty selection.

In single-operator vaults, the operator can also act as curator. In immutable vaults, key parameters are locked at deployment, removing ongoing curator control: this reduces governance risk but also removes flexibility.

### Interactions and Vault Configuration

You don’t need every internal detail, but you should know the main pieces you are indirectly steering and the key functions involved.

* **Vault and VaultFactory / configurator**

The vault holds collateral, tracks deposits and withdrawals, and enforces epoch-based exits. New vaults are typically created through a configurator that wraps the factories, for example a helper like `VaultConfigurator.create(initParams)` which, under the hood, calls `VaultFactory` and related factories to deploy the `Vault`, its `Delegator`, and its `Slasher`.

* **Delegator (stake allocation)**

The Delegator decides how vault stake is allocated across networks and operators. As a curator you mainly use functions such as `setNetworkLimit()` to define how much stake this vault can send to a network, and `setOperatorNetworkLimit()` or `setOperatorNetworkShares()` to shape stake per operator, depending on the Delegator type.

* **Slasher (penalties)**

The Slasher applies penalties when a network requests them (via a function like `slash()`). As curator you choose the Slasher type (instant or vetoed) and its timing parameters, such as the veto window, when you create the vault.

* **Burner (what happens to slashed collateral)**

The Burner is a contract address you pass when the vault is created. It decides what happens to slashed collateral: burn, redistribute, send to a treasury or insurance pool, or route to custom logic.

You also rely on:

* an **OperatorRegistry** and **NetworkRegistry**, which define which operators and networks exist

* **opt-in services** (for example calls like `OperatorVaultOptInService.optIn(vault)` and `OperatorNetworkOptInService.optIn(network)`) so that operators can receive stake from your vault once you allocate it

### Vault Strategy

Think of your work in three phases: design, deploy, and wire.

#### Design the policy

First, decide what the vault is supposed to do, in plain language:

* which networks you want to support

* how diversified or concentrated you want to be across operators

* ceilings per network and per operator

* whether slashing should be instant or have a short veto window

* how you expect rewards and risk to trade off

This is the document stakers and operators will read. Everything else is just encoding this policy on chain.

#### Deploy the vault

Next, you create the actual vault and its modules in a single step with a configurator call, for example:

`solidity

(Vault vault, address delegator, address slasher) =

VaultConfigurator.create(initParams);

`

In the `initParams` you choose, among other things:

* the collateral token

* the vault epoch duration

* the Delegator type (multi-network, single-network, operator-specific, etc.)

* the Slasher type (instant or vetoed) and, for vetoed flows, the veto duration

* the Burner contract that will handle slashed collateral

* access control, such as whether deposits are public or allowlisted

This is where you lock in the big structural choices: what the vault secures, how fast people can exit, which delegation topology it uses, and how slashing is handled.

#### Wire stake limits and allocations

Once the vault exists, you configure how it actually allocates stake.

In practice that means:

* For each network you want to support, setting a vault-side limit with a call like `delegator.setNetworkLimit(subnetwork, amount)` which says “this vault can send up to this much stake to this network or subnetwork”.

* After operators have opted into your vault and into those networks, setting their allocations using, depending on the Delegator type: `setOperatorNetworkLimit(subnetwork, operator, amount)` for hard caps, or `setOperatorNetworkShares(subnetwork, operator, shares)` for share-based routing.

These limit and share calls are the core knobs you use to express your strategy on chain.

### Managing Stake

Once the vault is live, your job is mostly careful, occasional adjustments rather than constant tweaking.

Typical ongoing actions:

* revisiting network limits and operator allocations if performance, risk, or demand changes

* nudging the strategy toward more or less concentration, by changing limits or shares rather than redeploying the entire vault

* keeping the written policy up to date with any material changes you make on chain

You generally do **not** need to touch the factories again. Most day-to-day stewardship happens through the Delegator functions that set limits and shares, and through off-chain communication when you add or remove networks and operators.

### Risk and Timing

Even with a good strategy, the details of timing and partners matter. A few simple checks go a long way.

#### Collateral and reward quality

* Make sure the collateral token you pick at vault creation has clear economic value and reasonable liquidity.

* Prefer networks that offer rewards that match the risk taken: protocol fees, revenues from external clients, or controlled token inflation with a clear purpose.

If the collateral is low quality and networks do not pay fairly, you risk running a vault that takes real slashing risk while barely compensating stakers.

#### Epochs and veto windows

* The vault epoch duration you set at creation defines how long withdrawals take and how long stake remains slashable after it is “captured” by a network.

* If you choose a vetoed Slasher, keep the veto window well below the vault epoch. Networks need time to detect misbehavior, submit a slash, and wait out the veto period before the vault epoch ends.

A simple mental model:

> network’s own epoch and proof delay

>

> plus the veto window (if any)

>

> plus the time it takes to submit and finalize the slash

>

> should fit comfortably inside the vault epoch

If that does not hold, networks may not be able to slash in time, and the economic guarantees you think you are providing become weaker.

#### Network and operator choices

The settings you choose in `setNetworkLimit`, `setOperatorNetworkLimit`, and `setOperatorNetworkShares` express your risk appetite.

* Treat the network limit as a risk budget for that network. Conservative vaults use lower limits and fewer networks; more aggressive vaults use higher limits and more networks, but should be explicit about correlated risk.

* When you allocate to operators, avoid over-concentrating on a single one unless that is very clearly part of the thesis. Slashing events will hit stakers in proportion to those allocations.

Your operator and network choices affect not just returns, but your reputation as a curator.

#### Contract health and extreme cases

* Be careful when changing access control and deposit limits to avoid locking the vault unintentionally.

* If the vault ever experiences a full (one hundred percent) slashing event, it is often cleaner to deploy a new vault, rather than trying to reuse the same one repeatedly. The history stays clear and future stakers know exactly what they are opting into.

* If you use fee-on-transfer collateral together with redistribution of slashed funds, be aware that the fee logic will introduce unavoidable losses during redistribution; that trade-off should be explicit in your policy.

### Vault Profiles

The same contracts and functions can describe very different vault “shapes”. Two common ones:

#### Diversified and conservative

* Several networks with moderate network limits

* Many operators, each with modest per-operator limits or fairly even shares

* A vetoed Slasher with a resolver set and a longer vault epoch

* Focus on capital preservation and strong guarantees over maximum throughput

#### Throughput and concentration

* Fewer networks with higher network limits

* A smaller set of top-tier operators with larger limits or shares

* An instant Slasher and a medium or shorter epoch

* Focus on fast settlement, high utilization, and more aggressive risk taking

You can treat these as anchor points and position your own vault somewhere in between, depending on who it is for.

### When active curation is minimal or not needed

Some vault designs intentionally minimize ongoing curator work.

* **Single-network, single-operator designs** often use a Delegator type that effectively hard-codes the network and operator at creation time. After a basic network limit is set, there may be little left to adjust.

* **Immutable, pre-configured vaults** are created once with a fixed configuration and no roles that can change core behavior later. Users opt into a static design rather than a curator’s future decisions.

In those cases, your job as the original curator is mostly to make sure the initial configuration and documentation are correct and to be transparent that the vault will not change over time.

## **Network**

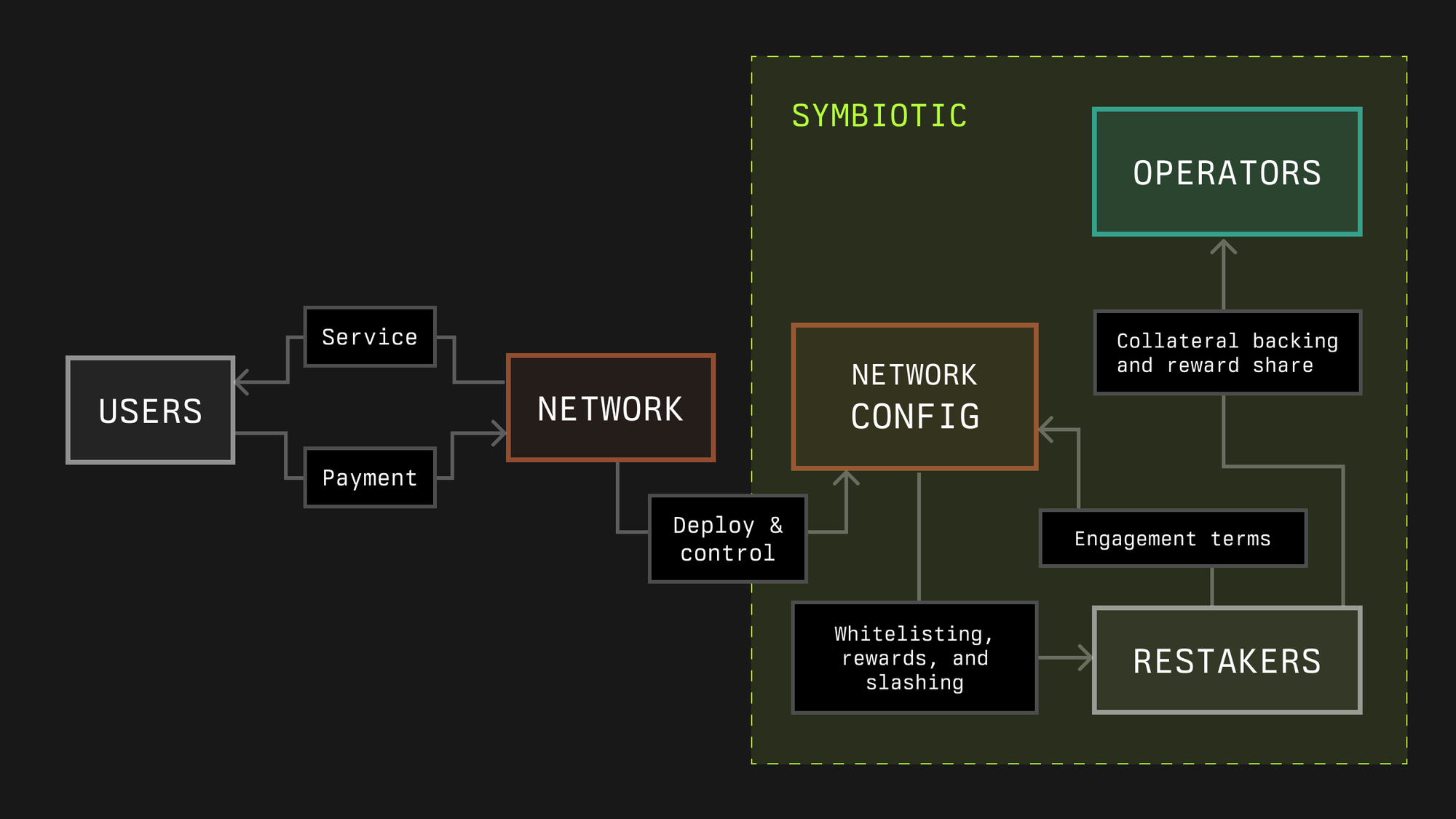

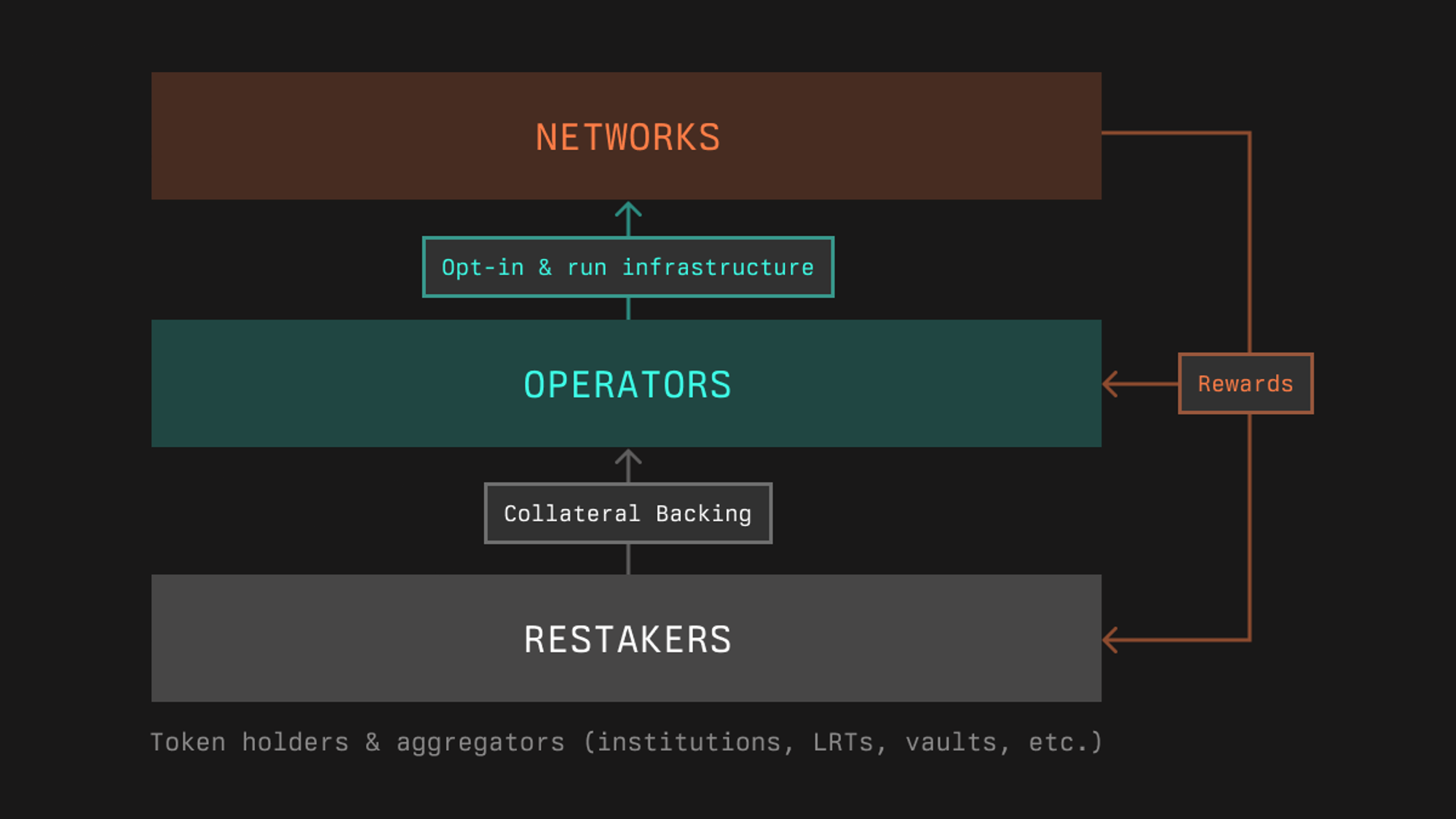

In Symbiotic, a Network is any protocol that requires a decentralized infrastructure network to deliver a service in the crypto economy, such as enabling developers to launch decentralized applications by validating and ordering transactions, providing off-chain data to applications, or providing users with guarantees about cross-network interactions.

Decentralized infrastructure networks can utilize Symbiotic to flexibly source their security in the form of operators and economic backing. In some cases, protocols may consist of multiple sub-networks with different infrastructure roles. The Symbiotic protocol’s modular design allows developers of such protocols to define the rules of engagement that participants need to opt into for any of these sub-networks.

## **Technical Overview**

In Symbiotic, networks are represented through a network address (either a contract or multisig) and a middleware, which can incorporate custom and slashing logic. The core protocol’s fundamental functionalities encompass slashing operators and rewarding both stakers and operators.

Middleware contracts integrate with Symbiotic Core for stake capture, validator set management, slashing, and optional rewards accounting. Optional means that rewards logic can live in the middleware, while the Network always defines the existence, funding, and source of rewards.

The network also has its own operator set, which provides services to the network. The network’s software produces work, emits messages to be attested, and participates in epochs. Here the network admin defines voting power rules and thresholds, message formats, participation and liveness requirements, dispute inputs, and Relay compatibility if it wants cross chain verification.

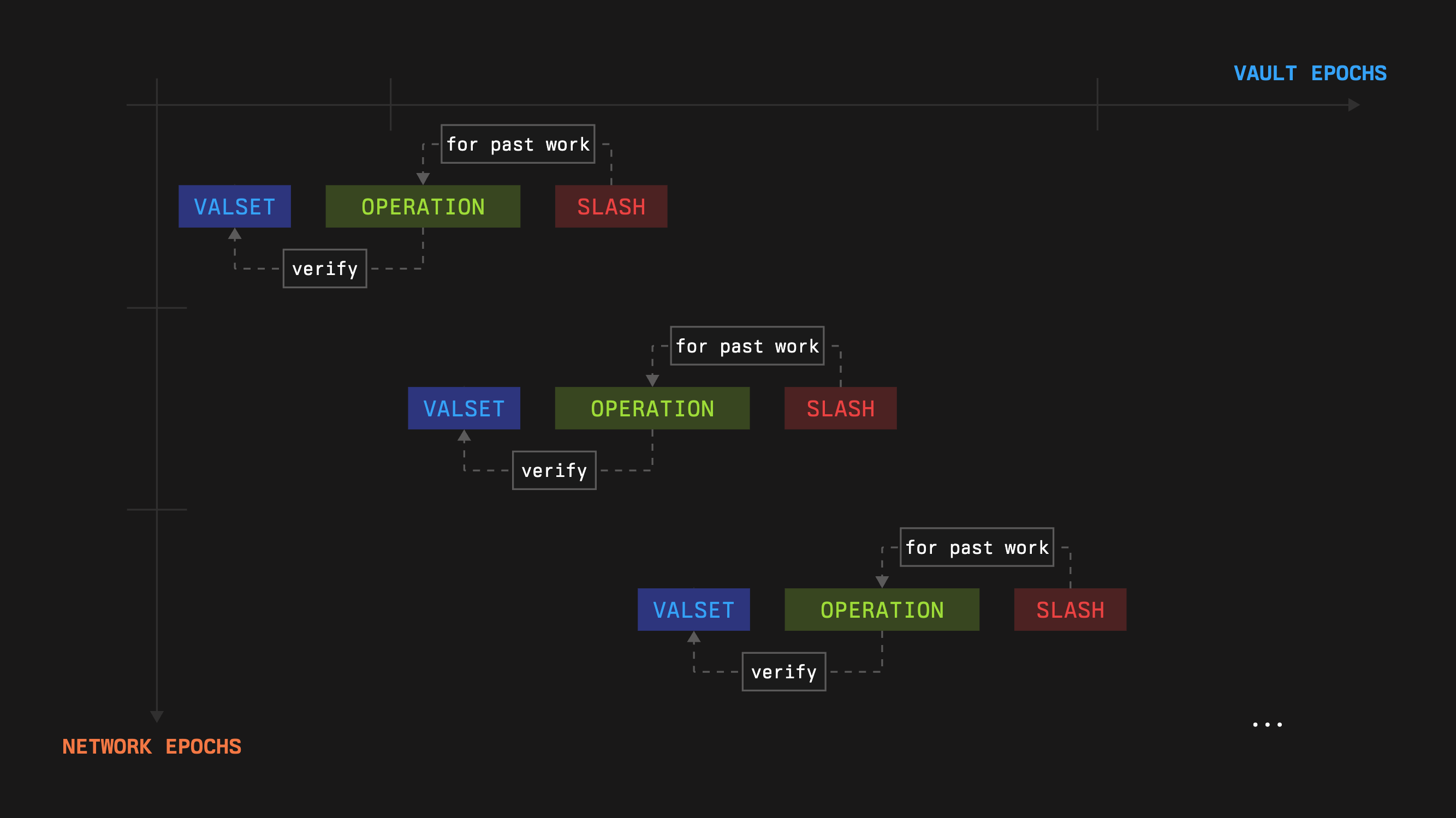

### **Epoch**

A network epoch (let’s name it `NETWORK_EPOCHNETWORK_EPOCH`) is a period while a certain operator set, obtained given the captured stake, operates for the good of the network. The epoch plus the vault’s veto and execute phases’ durations should not exceed the duration of the vault’s epoch to ensure that withdrawals do not impact the captured stake (however, the conditions can be softer in practice).

[See Vault Accounting Details](/learn/core-concepts/vault#accounting-and-epochs)

A valid operator set means the validator set captured for the current network epoch is the reference set used for verification and slashing during that epoch. While it remains valid, on chain checks verify signatures against that set and its associated weights, and any slashing decisions are made with respect to those same weights.

### **Staking**

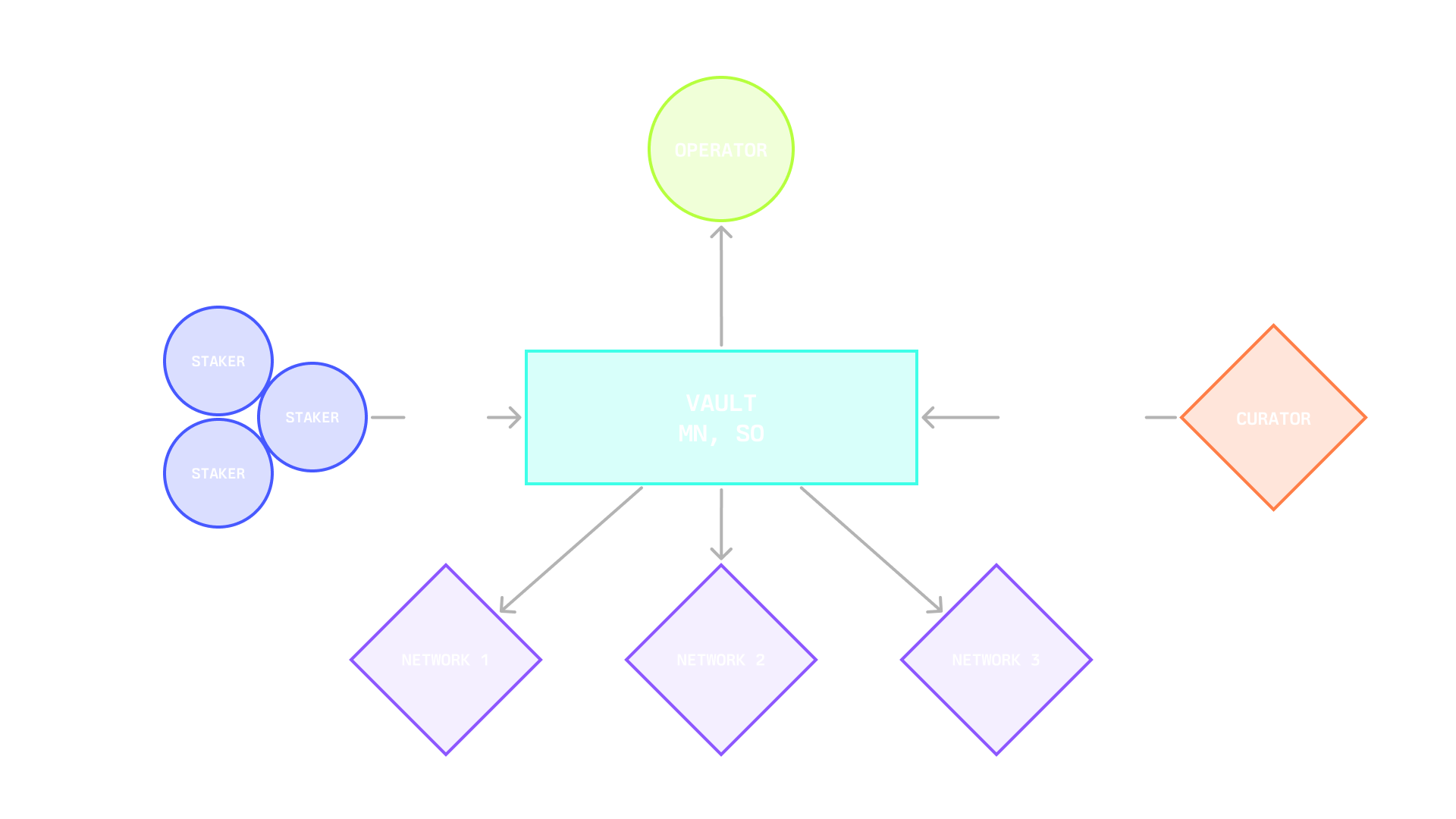

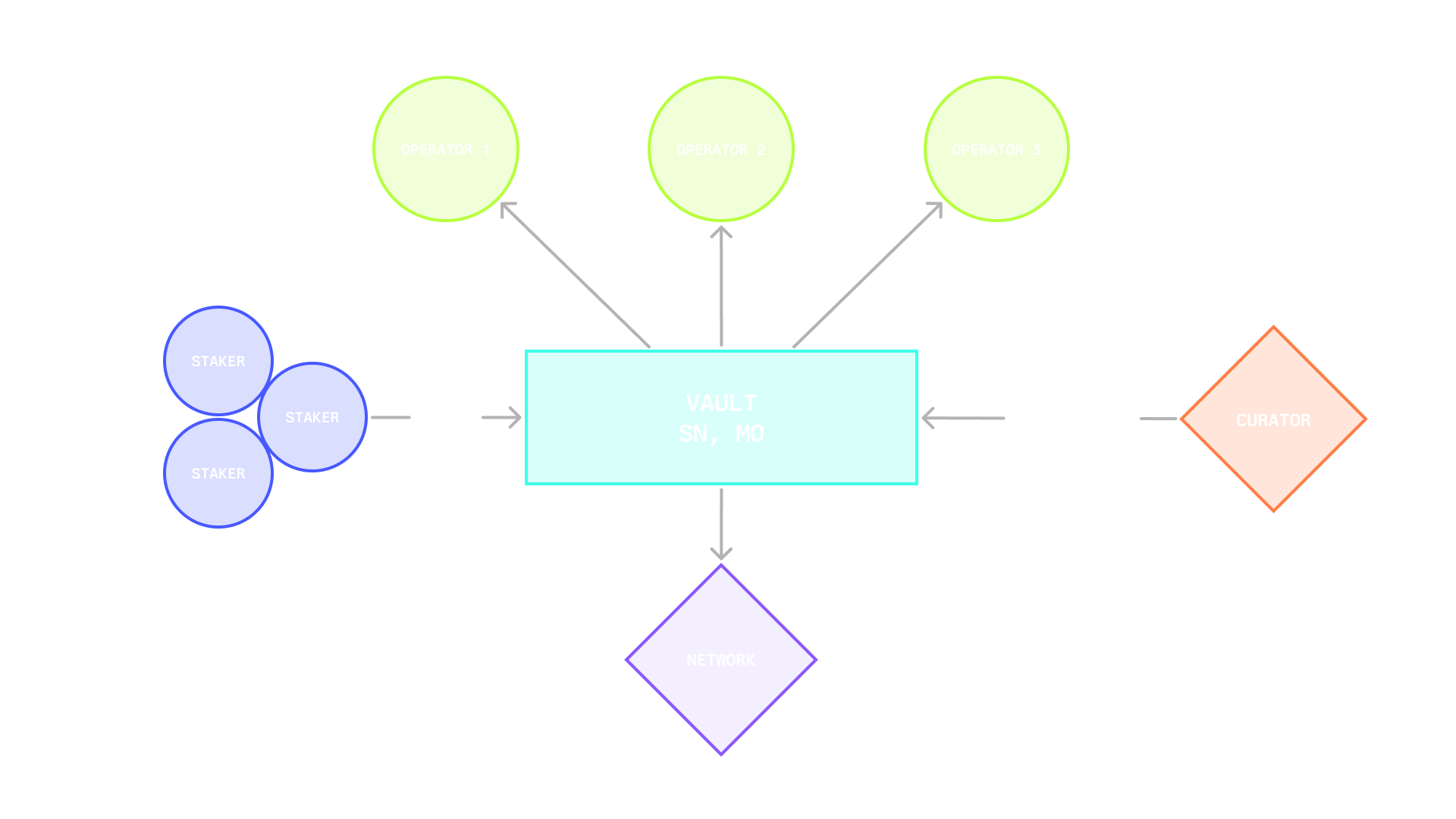

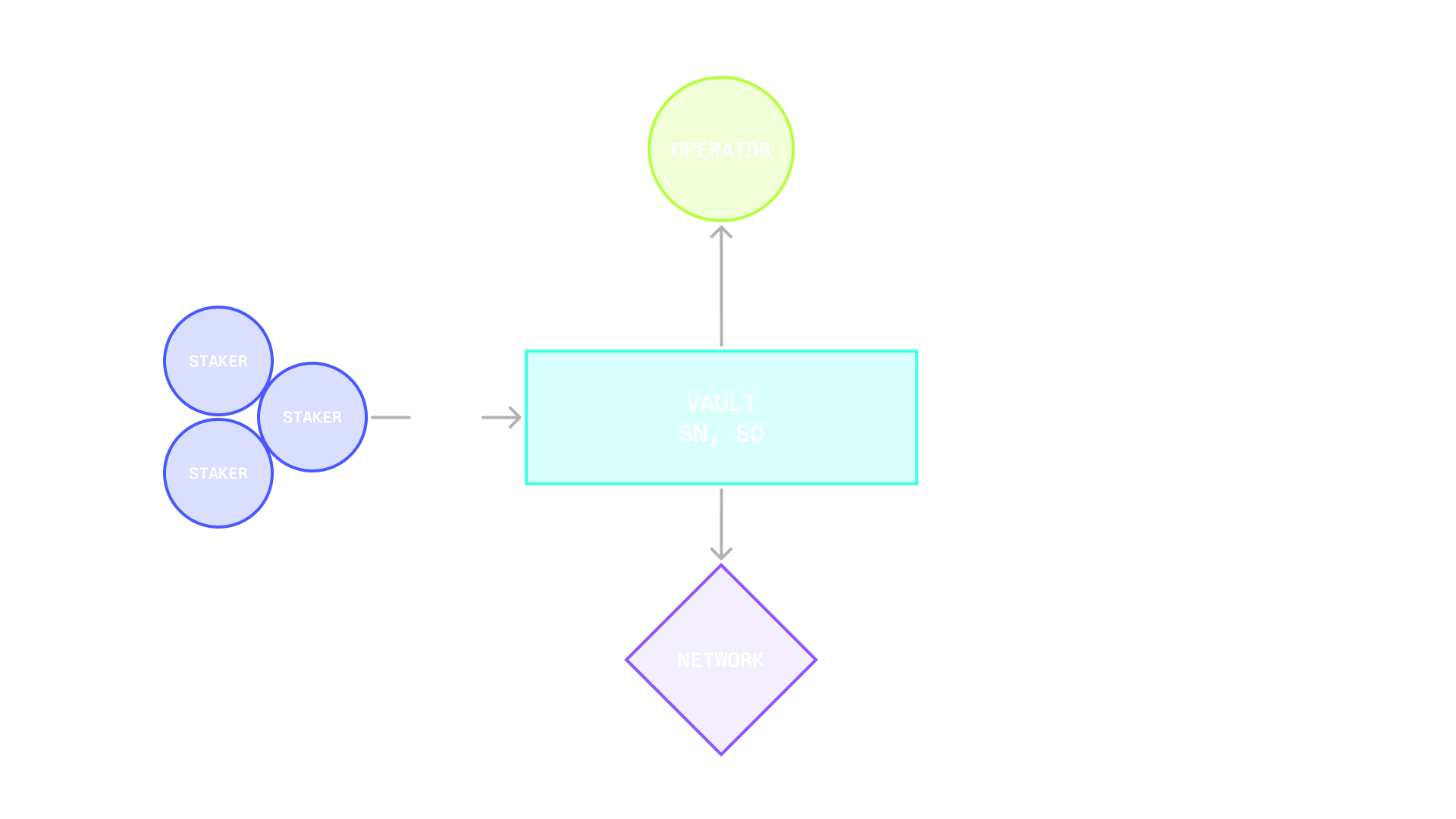

The vault allocates stakes by setting limits for networks and operators.

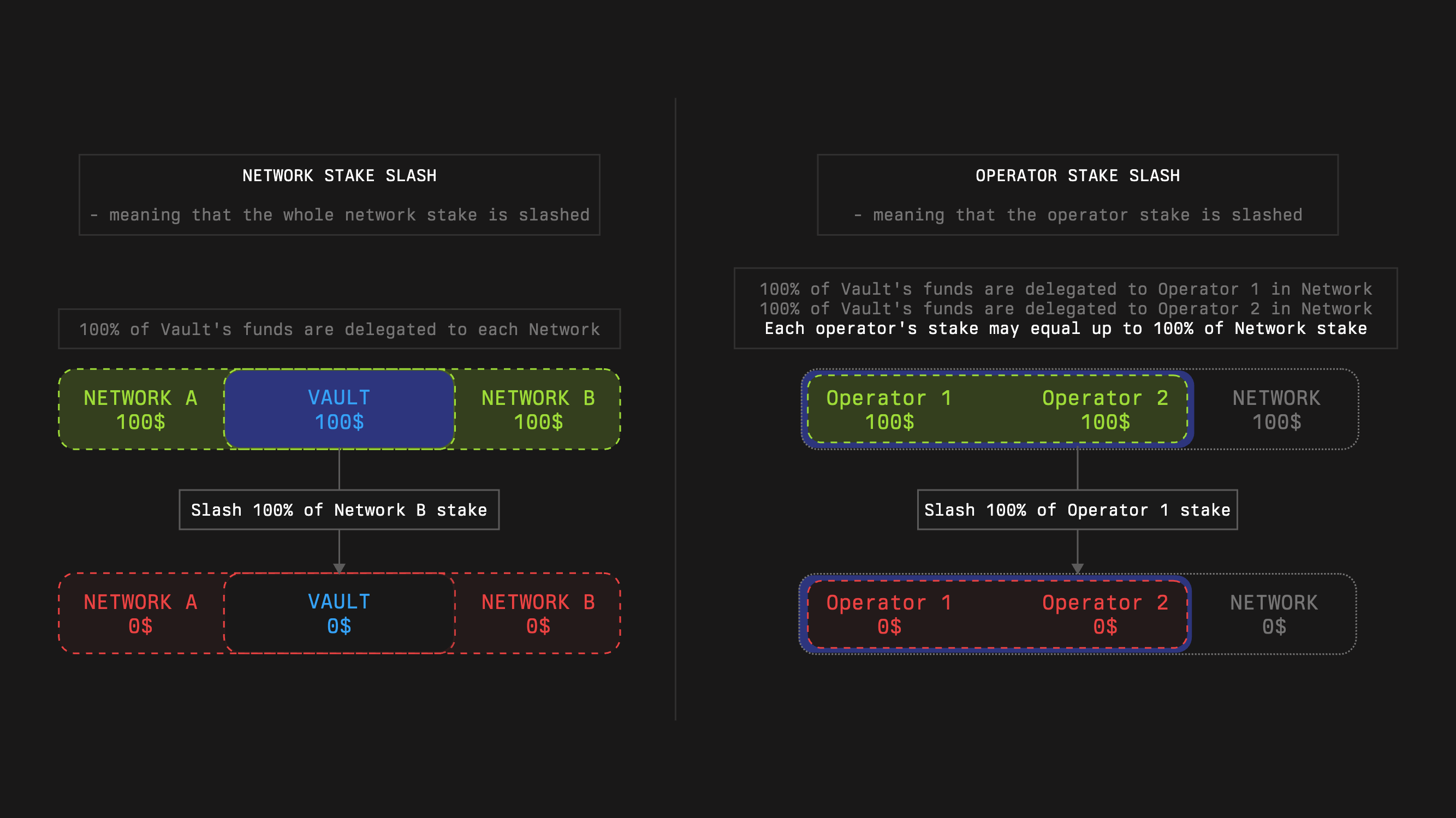

Let the Vault be *V*, the Delegator module of the vault is *D* and the Slasher module is *S*.

[See Stake Allocating Details](/learn/core-concepts/vault#delegation)

Given the current active balance of the vault and the limits, we can capture the stake for the subsequent network epoch: `networkOperatorStake=D.stake(network,operator)`

#### **Subnetworks**

Instead of creating multiple instances of a network, the Symbiotic protocol allows the creation of multiple subnetworks within the same network. This is similar to an operator having multiple keys instead of creating several instances of the operator. All limits, stakes, and slashing requests are handled by subnetworks, not the main network. This approach diversifies the network’s stake across different staking mechanics. For example, one subnetwork can have high limits and a trusted resolver in the Slasher module, while another subnetwork can have lower limits but no resolver in the Slasher module.

The final ID is just a concatenation of the network’s address and the provided `identifier`, so collision is not possible.

For simplicity, we sometimes omit the presence of subnetworks and just use the term network.

#### **Limits**

Limits are set in the vault, and the network cannot control this process (unless the vault is managed by the network). However, the implementation prevents the vault from removing previously given slashing guarantees.

Additionally, the network can limit the maximum amount of stake it wants to use via the `D.setMaxNetworkLimit()` method.

#### **Staking Lifecycle:**

1. The network registers by calling `NetworkRegistry.registerNetwork()`.

2. Operators register by calling `OperatorRegistry.registerOperator()`.

3. The operators must opt into the vault and the network.

4. Stakers deposit funds into the vault.

5. The network sets a maximum stake amount for the vault by calling `D.setMaxNetworkLimit(identifier, amount)`.

6. The `NETWORK_LIMIT_SET_ROLE` holder defines the stake limit for the network.

7. The `OPERATOR_NETWORK_LIMIT_SET_ROLE` holder defines the stake limit for the operator-network pair.

The current stake amount cannot be withdrawn for at least one epoch, although this restriction does not apply to cross-slashing.

#### **Operator Set**

The network has the flexibility to configure an operator set within the middleware, later to be used as a validator set (a.k.a. valset) for its validating.

The following functions could be useful:

* `D.stakeAt(subnetwork, operator, timestamp, hints)`: Determines minimum stake eligibility. Note that the sum of operators’ stakes may exceed the network’s total stake, depending on the network’s and operators’ limits in the delegator module.

* `OptInService.isOptedInAt(operator, subnetwork, timestamp, hint)`: Checks the opt-in status.

### **Slashing**

[See Slashing Details](/learn/core-concepts/slashing)

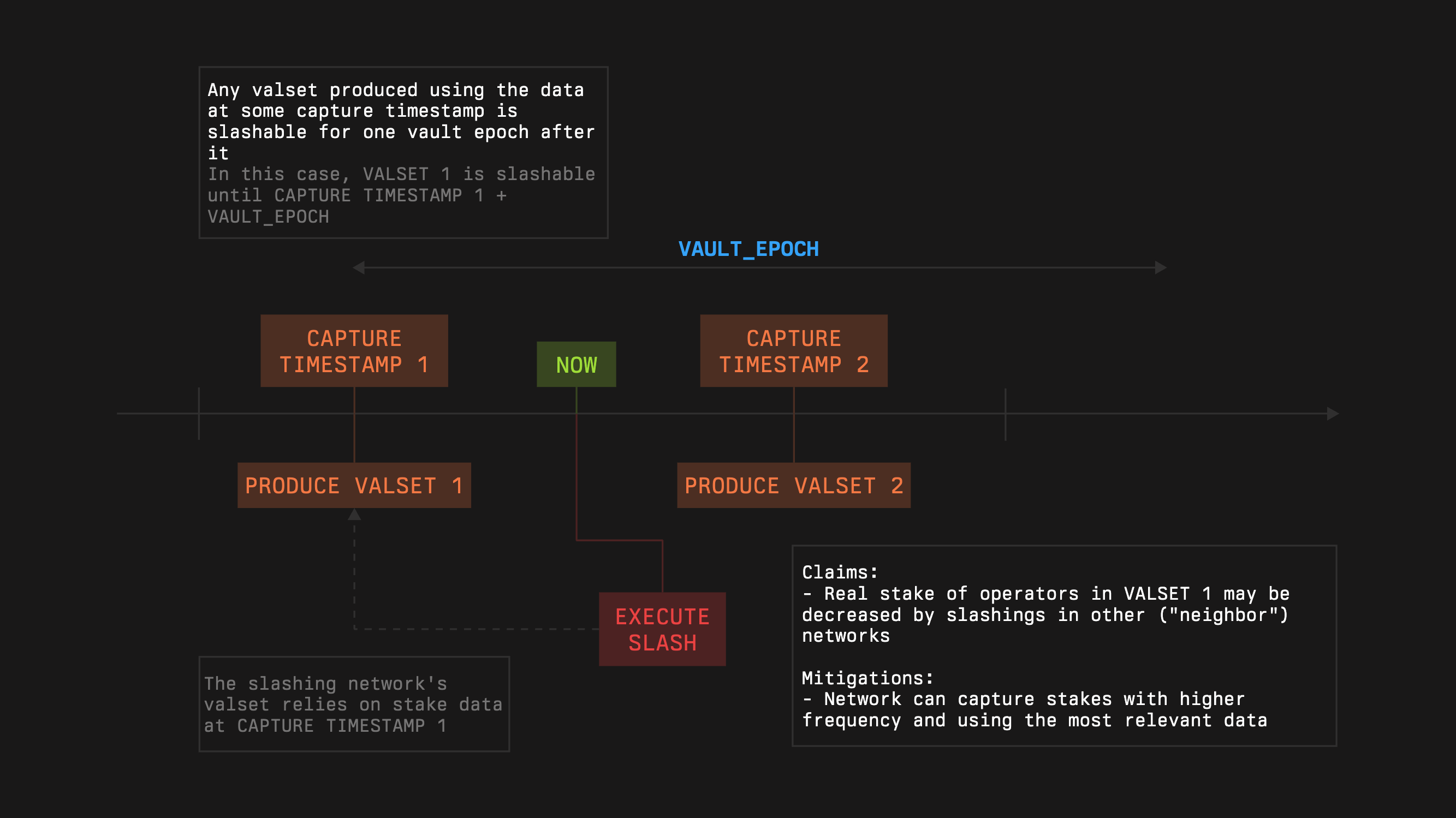

For each operator, the network can obtain its stake which will be valid during `d=vaultEpochd`. Through its middleware, the Network initiates slashing when provable misbehavior occurs according to Network‑defined rules. Slashing protects stakers from dishonest or idle operators and protects Networks from operators taking stake without performing required work. Symbiotic Core enforces objective bounds so only stake guaranteed at capture can be burned.

A slashing request must reference a capture timestamp that is no more than one vault epoch old, not exactly equal to the epoch boundary. Requests can arrive at any time within this sliding window. Requiring equality would cause legitimate slashes to fail around boundaries.

Note that the actual slashed amount may be less than the requested one.

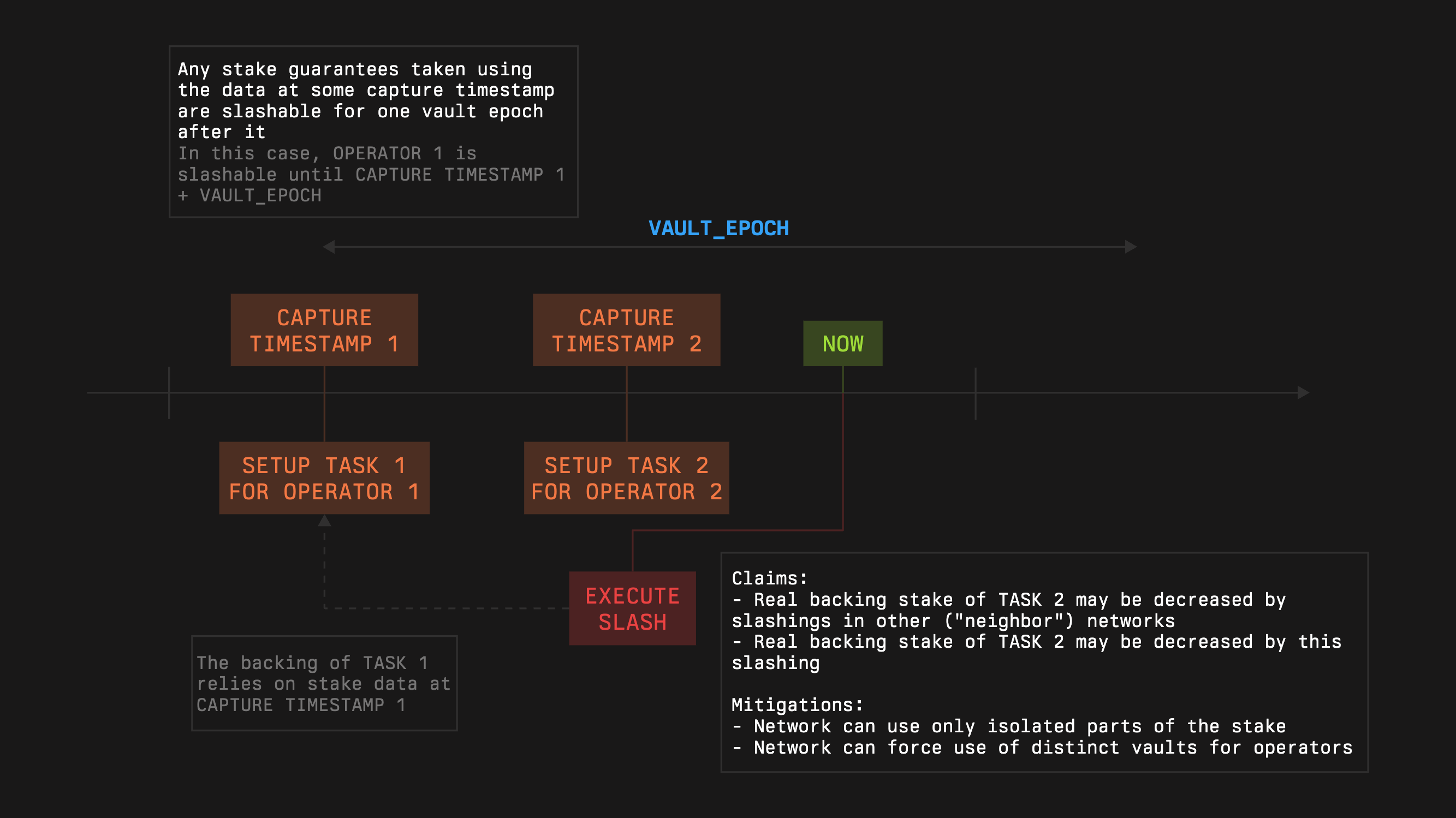

1. This may be influenced by cross-slashing.

1. This may be influenced by slashings by the network itself, as the consequent valsets may depend on the stake used for the creation of the previous valsets.

1. In the case of a task-like system, where each task is backed by the corresponding operator’s stake, this may be influenced by slashings by the network itself if the operators have a pooled stake.

The network can slash the operator within the vault only if

1. The operator is opted into the vault

2. The operator is opted into the network

To initiate a slashing process, a network should call:

1. `slash(subnetwork, operator, amount, captureTimestamp, hints)` for the Slasher module.

2. `requestSlash(subnetwork, operator, amount, captureTimestamp, hints)` for the VetoSlasher module.

The module will check the provided guarantees at the `*captureTimestamp*`, denoted as `*G.*` It also calculates cumulative slashings from the `captureTimestamp` to the current moment, denoted as `*C*`. It is guaranteed that for every correct `captureTimestamp`, `C≤G`. The module will allow slashing no more than `G−C` to justify the given guarantees.

### **Operating Lifecycle**

A network can use flexible mechanics to keep its operator set state up-to-date, e.g., it’s convenient to use a conveyor approach for updating the stakes while keeping slashing guarantees for every particular version of the operator set:

1. At the beginning of every epoch the network can capture the state from vaults and their stake amount (this doesn’t require any on-chain interactions).

2. After this, the network will have slashing guarantees for one vault epoch duration, so it can use this state at most for one vault epoch.

3. When the epoch finishes and a slashing incident has taken place, the network will have time equal to the vault epoch duration minus the network epoch to request-veto-execute slash and go back to step 1 in parallel.

### **Rewards**

In Symbiotic, rewards are categorized into:

* Operator rewards

* Staker rewards

#### **Operator Rewards**

The network distributes the operator rewards at its discretion. Here are three examples:

1. The network performs off-chain calculations to determine the reward distributions. After calculating the rewards, the network executes batch transfers to distribute the rewards in a consolidated manner.

2. The network performs off-chain calculations to determine rewards and generates a Merkle tree, allowing operators to claim their rewards.

3. The network performs on-chain reward calculations within its middleware to determine the distribution of rewards.

#### **Source of Data for Network On-Chain Reward Calculations**

[For each epoch, networks obtain their staking information through our system.](https://github.com/symbioticfi/rewards) Additionally, all operators register through the network, providing necessary details such as commission rates, fixed payments, and other relevant conditions. This registration process ensures that networks have the required data to perform accurate on-chain reward calculations in their middleware.

#### **Staker Rewards**

[See Staker Rewards Details](/learn/core-concepts/rewards)

### **Relay SDK Integration**

All of this can be cumbersome to scope, implement, and maintain from scratch. That is why Symbiotic provides the Relay SDK, a set of contracts and off chain components that let networks capture stake through Symbiotic, track operator sets and voting power, aggregate signatures, and plug into slashing without rebuilding their own verification layer.

Using the Relay SDK, a network can verify the same work across multiple EVM chains, aggregate operator signatures off chain and verify them once on chain, and significantly reduce verification costs while keeping its existing governance, message formats, and slashing rules unchanged.

## **Operator**

Operators run the software that keeps decentralized networks alive. They include node operators or validators that run consensus and network-specific binaries, sign messages for bridging and oracles, or strategy operators such as risk managers and AI agents that execute DeFi strategies on behalf of a network.

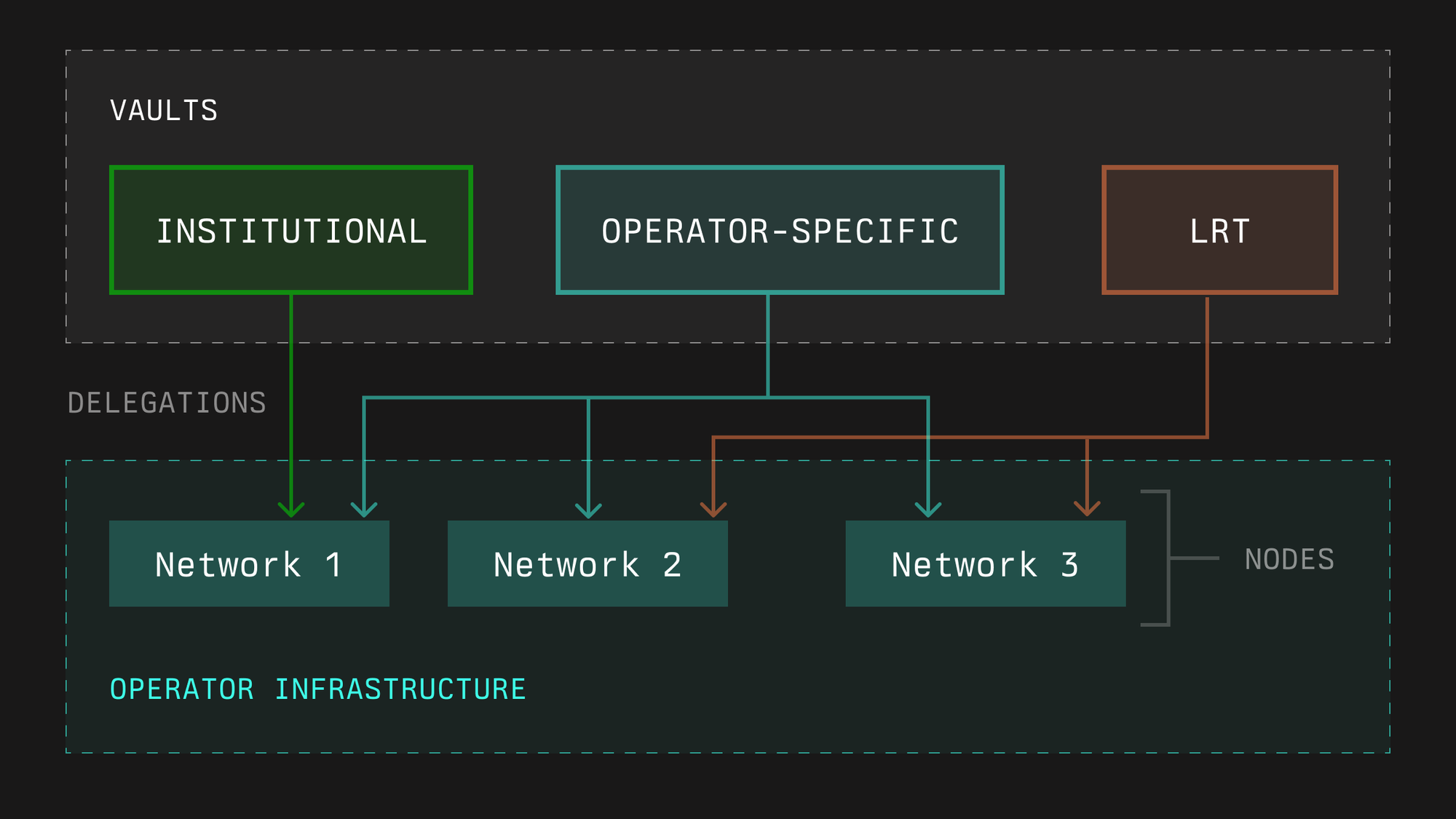

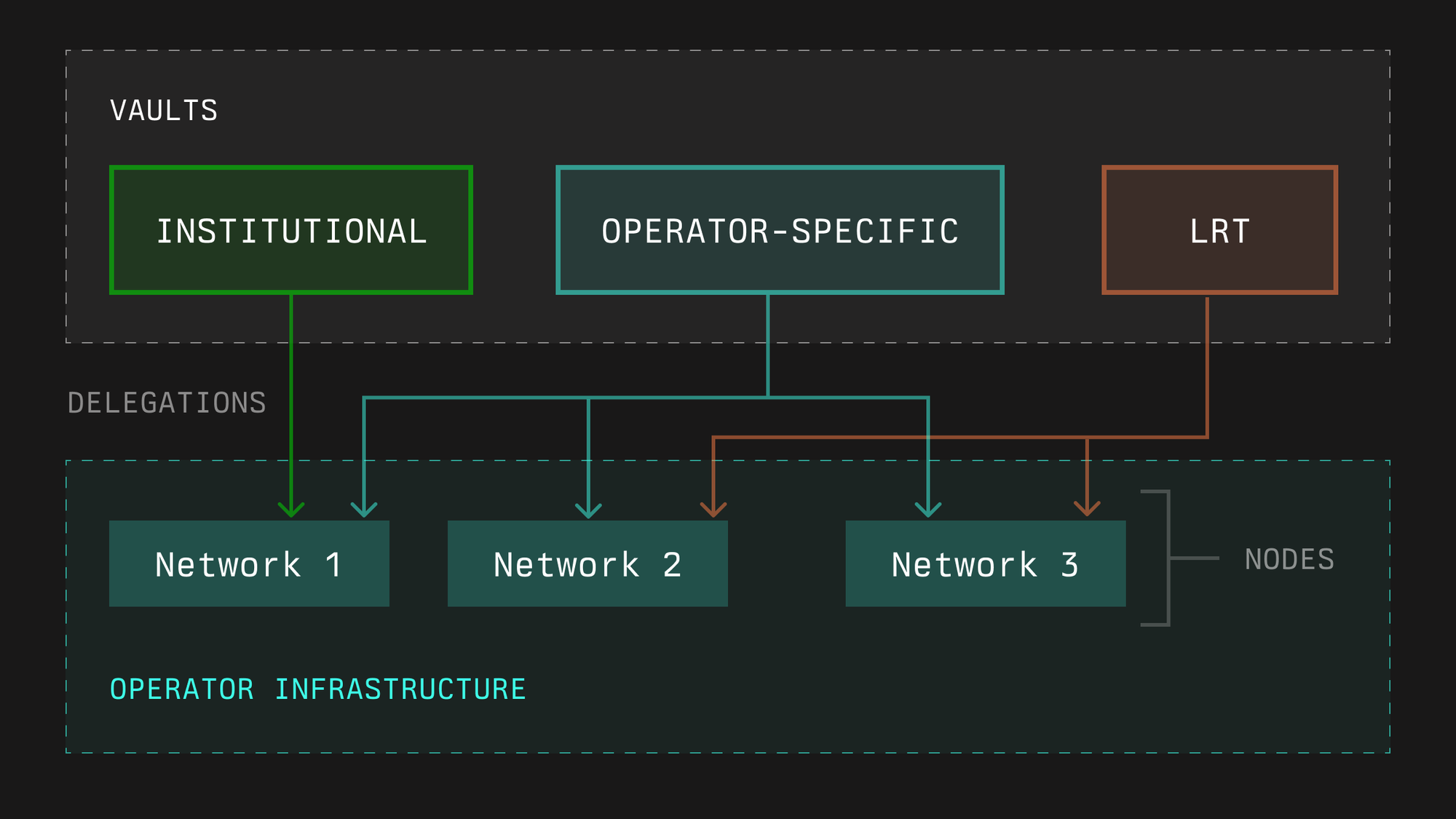

Within Symbiotic, operators can receive stake from different vaults and route it to the same set of nodes for a given network. The protocol maintains a registry of operators and records their activity so networks and curators can make informed choices. The registry covers which networks an operator has opted into, which vaults are connected and how much restaked collateral came from them, and a history of slashes and other on chain interactions.

This setup lets operators aggregate stake from many sources, including institutional vaults, operator specific vaults, or LRTs with different risk profiles, without spinning up separate infrastructure for each one. A single node stack per network can secure multiple partners, as long as all parties have opted in.

In Symbiotic, an operator is either an externally owned account or a contract registered in the OperatorRegistry.

### Operator onboarding

At a high level, onboarding an operator involves three steps.

1. Register the operator entity in the operator registry so it can be referenced by vaults and networks: Call `OperatorRegistry.registerOperator()` in `OperatorRegistry`.

2. Opt into the networks the operator wants to serve. Each network decides whether to include the operator in its active set based on criteria such as performance history, reputation, stake, and reliability. This is achieved by calling the `optIn()` method in `OperatorNetworkOptInService` .

3. Opt into the vaults that may allocate stake to that operator. This is achieved by calling the `optIn()` method in `OperatorVaultOptInService`. Curators then configure limits or shares so the Delegator can route stake to the operator within each network’s bounds. The address that holds `OPERATOR_NETWORK_SHARES_SET_ROLE` or `OPERATOR_NETWORK_LIMIT_SET_ROLE` for the vault assigns stake to the operator by calling either:

* `D.setOperatorNetworkShares(...)`, or

* `D.setOperatorNetworkLimit(...)`

depending on the Delegator type used by the vault.

Stake becomes eligible for slashing only when the operator has opted into both the network and the vault at the time stake is captured for an epoch.

### Working with Vaults and Networks

#### Vaults

Vaults are where stake lives. Curators decide which operators are admissible for a vault and how much stake each one can receive. They set per operator limits or shares and may adjust them as conditions change. The Delegator module uses these settings, together with opt ins, to determine how much effective stake each operator has per network.

#### Networks

Networks are where operators perform work. An operator opts into a network in order to validate it or to provide a defined service. Based on its own criteria, each network independently decides whether to include the operator in the active operator set. The network’s software produces work, emits messages or commitments to be attested, and participates in epochs. Here the network defines voting power rules and thresholds, message formats, participation and liveness requirements, dispute inputs, and how it integrates with the Relay if it needs cross chain verification.

#### Aggregation

For a single network, an operator can combine stake from multiple vaults into one node stack as long as:

* the operator has opted into that network

* the operator has opted into those vaults

* curators have allocated stake to the operator within each network limit

This allows operators to build one hardened infrastructure per network and receive stake from many partners without fragmenting their setup.

#### Subnetworks and Keys

Some networks split responsibilities into subnetworks. Limits, stake capture, and any penalties apply per subnetwork. Operators should plan key management and operations with that boundary in mind, for example by running distinct keys or processes per subnetwork where needed.

### Relay integration

All of the above can be implemented with custom network logic, but wiring cross chain verification, aggregation, and stake capture from scratch is complex. Symbiotic provides the Relay SDK so networks and operators can plug into a common framework instead.

If a network uses the Relay SDK:

* The Relay uses the operator registry and voting power from Symbiotic to build the operator set for that network.

* Operators can run a small Relay sidecar that helps collect signatures, aggregate them, and submit commitments so verification remains efficient across EVM chains.

* The same operator set and stake that secure the network can be reused to attest on multiple chains, reducing costs and integration effort while keeping the network’s governance and rules unchanged.

From the operator perspective, Relay integration mainly means running an additional, lightweight process that works alongside their existing nodes and keys, rather than rewriting their own cross chain logic.

### Penalties and Slashing

Once an operator has opted into a vault and a network, and stake has been captured for an epoch, that stake becomes subject to slashing according to the network rules and the vault configuration.

If an operator fails to perform services according to those rules, the network middleware can raise a slashing request against the operator’s stake. On Ethereum style systems this includes faults such as double signing or other consensus violations. The vault’s Slasher module validates slashing requests and, if they are correct and within the defined guarantees, applies penalties to the operator’s stake and invokes the vault’s Burner to decide what happens to the penalized collateral.

Some setups allow immediate execution of valid slashes, while others introduce a short veto or review window, depending on the Slasher type chosen by the curator and the network.

### Rewards

Operators need to be compensated for the services they provide and the risk they take. Networks pay operators from the value they generate, for example protocol fees, payments from external clients who use their services, or token inflation allocated to security and operations.

Symbiotic’s rewards framework gives networks several ways to route these payments:

* the network can calculate rewards off chain and send periodic batch transfers to operators

* it can calculate rewards off chain and publish a Merkle tree so each operator claims its share

* or it can keep reward accounting fully on chain in its middleware and distribute directly from that state

In every case, the goal is the same: operators are paid in a way that matches the work they do, the stake they are trusted with, and the risk profile of the networks they secure.

## **Rewards**

Rewards are payments that Networks make to stakers and operators in exchange for security and work.

* **Stakers** provide collateral that backs operator behavior and is at risk of slashing.

* **Operators** run the infrastructure or strategies that the Network depends on: validators, relay/bridge nodes, risk engines, or DeFi execution logic.

Rewards compensate: